|

|

CHAPTERS |

CONTENTS |

|

[01] |

THE BUDDHA - FROM BIRTH TO

RENUNCIATION |

|

[02] |

HIS STRUGGLE FOR ENLIGHTENMENT |

|

[03] |

THE BUDDHAHOOD |

|

[04] |

AFTER THE ENLIGHTENMENT |

|

[05] |

THE INVITATION TO EXPOUND THE

DHAMMA |

|

[06] |

DHAMMACAKKAPPAVATTANA SUTTA - THE

FIRST DISCOURSE |

|

[07] |

THE TEACHING OF THE DHAMMA |

|

[08] |

THE BUDDHA AND HIS RELATIVES |

|

[09] |

THE BUDDHA AND HIS RELATIVES

(Continued) |

|

[10] |

THE BUDDHA'S CHIEF OPPONENTS AND

SUPPORTERS |

|

[11] |

THE BUDDHA'S ROYAL PATRONS |

|

[12] |

THE BUDDHA'S MINISTRY |

|

[13] |

THE BUDDHA'S DAILY ROUTINE |

|

[14] |

THE BUDDHA'S PARINIBBĀNA (DEATH) |

|

[15] |

THE TEACHINGS OF THE BUDDHA |

|

[16] |

SOME SALIENT CHARACTERISTICS OF

BUDDHISM |

|

[17] |

THE FOUR NOBLE TRUTHS |

|

[18] |

KAMMA |

|

[19] |

WHAT IS KAMMA? |

|

[20] |

THE WORKING OF KAMMA |

|

[21] |

NATURE OF KAMMA |

|

[22] |

WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF LIFE ? |

|

[23] |

THE BUDDHA ON THE SO-CALLED

CREATOR-GOD |

|

[24] |

REASONS TO BELIEVE IN REBIRTH |

|

[25] |

THE WHEEL OF LIFE -

PATICCA-SAMUPPĀDA |

|

[26] |

MODES OF BIRTH AND DEATH |

|

[27] |

PLANES OF EXISTENCE |

|

[28] |

HOW REBIRTH TAKES PLACE |

|

[29] |

WHAT IS IT THAT IS REBORN?

(No-Soul) |

|

[30] |

MORAL RESPONSIBILITY |

|

[31] |

KAMMIC DESCENT AND KAMMIC ASCENT |

|

[32] |

A NOTE ON THE DOCTRINE OF KAMMA AND

REBIRTH IN THE WEST |

|

[33] |

NIBBĀNA |

|

[34] |

CHARACTERISTICS OF NIBBĀNA |

|

[35] |

THE WAY TO NIBBĀNA (I) |

|

[36] |

THE WAY TO NIBBĀNA (II) -

MEDITATION |

|

[37] |

NĪVARANA OR HINDRANCES |

|

[38] |

THE WAY TO NIBBĀNA (III) |

|

[39] |

THE STATE OF AN ARAHANT |

|

[40] |

THE BODHISATTA IDEAL |

|

[41] |

PĀRAMĪ - PERFECTIONS |

|

[42] |

BRAHMAVIHĀRA - THE SUBLIME STATES |

|

[43] |

EIGHT WORLDLY CONDITIONS |

|

[44] |

THE PROBLEMS OF LIFE |

-ooOoo-

Namo Tassa Bhagavato

Arahato Sammā-Sambuddhassa

Homage to Him, the Exalted, the Worthy, the Fully Enlightened One

-ooOoo-

INTRODUCTION

M any

valuable books have been written by Eastern and Western scholars,

Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike, to present the life and teachings

of the Buddha to those who are interested in Buddhism.

Amongst them one of the most popular

works is still The Light of Asia by Sir Edwin Arnold. Many

Western truth-seekers were attracted to Buddhism by this

world-famous poem.

Congratulations of Eastern and

Western Buddhists are due to the learned writers on their laudable

efforts to enlighten the readers on the Buddha-Dhamma.

This new treatise is another humble

attempt made by a member of the Order of the Sangha, based on the

Pāli Texts, commentaries, and traditions prevailing in Buddhist

countries, especially in Ceylon.

The first part of the book deals

with the Life of the Buddha, thc second with the Dhamma, the Pāli

term for His Doctrine.

*

The Buddha-Dhamma is a moral

and philosophical system which expounds a unique path of

Enlightenment, and is not a subject to be studied from a mere

academic standpoint.

The Doctrine is certainly to be

studied, more to be practised, and above all to be realized by

oneself.

Mere learning is of no avail without

actual practice. The learned man who does not practise the Dhamma,

the Buddha says, is like a colourful flower without scent.

He who does not study the Dhamma is

like a blind man. But, he who does not practise the Dhamma is

comparable to a library.

*

There are some hasty critics who

denounce Buddhism as a passive and inactive religion. This

unwarranted criticism is far from the truth.

The Buddha was the first most active

missionary in the world. He wandered from place to place for

forty-five years preaching His doctrine to the masses and the

intelligentsia. Till His last moment, He served humanity both by

example and by precept. His distinguished disciples followed suit,

penniless, they even travelled to distant lands to propagate the

Dhamma, expecting nothing in return.

"Strive on with diligence"

were the last words of the Buddha. No emancipation or purification

can be gained without personal striving. As such petitional or

intercessory prayers are denounced in Buddhism and in their stead is

meditation which leads to self-control, purification, and

enlightenment. Both meditation and service form salient

characteristics of Buddhism. In fact, all Buddhist nations grew up

in the cradle of Buddhism.

"Do no evil",

that is, be not a curse to oneself and others, was the Buddha's

first advice. This was followed by His second admonition ? "Do

good", that is, be a blessing to oneself and others. His final

exhortation was ? "Purify one's mind" -- which was the most

important and the most essential.

Can such a religion be termed

inactive and passive?

It may be mentioned that, amongst

the thirty-seven factors that lead to enlightenment (Bodhipakkhiya-Dhamma),

viriya or energy occurs nine times.

Clarifying His relationship with His

followers, the Buddha states:

"You yourselves should make the

exertion.

The Tathāgatas are mere teachers."

The Buddhas indicate the path and it

is left for us to follow that path to obtain our purification.

Self-exertion plays an important part in Buddhism.

"By oneself is one purified; by

oneself is one defiled."

*

Bound by rules and regulations,

Bhikkhus can be active in their own fields without trespassing their

limits, while lay followers can serve their religion, country and

the world in their own way, guided by their Buddhist principles.

Buddhism offers one way of life to

Bhikkhus and another to lay followers.

In one sense all Buddhists are

courageous warriors. They do fight, but not with weapons and bombs.

They do kill, but not innocent men, women and children.

With whom and with what do they

fight? Whom do they mercilessly kill?

They fight with themselves, for man

is the worst enemy of man. Mind is his worst foe and best friend.

Ruthlessly they kill the passions of lust, hatred and ignorance that

reside in this mind by morality, concentration and wisdom.

Those who prefer to battle with

passions alone in solitude are perfectly free to do so. Bhikkhus who

live in seclusion are noteworthy examples. To those contended ones,

solitude is happiness. Those who seek delight in battling with

life's problems living in the world and thus make a happy world

where men can live as ideal citizens in perfect peace and harmony,

can adopt that responsibility and that arduous course.

Man is not meant for Buddhism. But

Buddhism is meant for man.

*

According to Buddhism, it should be

stated that neither wealth nor poverty, if rightly viewed, can be an

obstacle towards being an ideal Buddhist. Anāthapindika, the

Buddha's best supporter, was a millionaire. Ghatikāra, who was

regarded even better than a king, was a penniless potter.

As Buddhism appeals to both the rich

and the poor it appeals equally to the masses and the

intelligentsia.

The common folk are attracted by the

devotional side of Buddhism and its simpler ethics while the

intellectuals are fascinated by the deeper teachings and mental

culture.

A casual visitor to a Buddhist

country, who enters a Buddhist temple for the first time, might get

the wrong impression that Buddhism is confined to rites and

ceremonies and is a superstitious religion which countenances

worship of images and trees.

Buddhism, being tolerant, does not

totally denounce such external forms of reverence as they are

necessary for the masses. One can see with what devotion they

perform such religious ceremonies. Their faith is increased thereby.

Buddhists kneel before the image and pay their respects to what that

image represents. Understanding Buddhists reflect on the virtues of

the Buddha. They seek not worldly or spiritual favours from the

image. The Bodhi-tree, on the other hand, is the symbol of

enlightenment.

What the Buddha expects from His

adherents are not these forms of obeisance but the actual observance

of His Teachings. "He who practises my teaching best, reveres me

most", is the advice of the Buddha.

An understanding Buddhist can

practise the Dhamma without external forms of homage. To follow the

Noble Eightfold Path neither temples nor images are absolutely

necessary.

*

Is it correct to say that Buddhism

is absolutely otherworldly although Buddhism posits a series of past

and future lives and an indefinite number of habitable planes?

The object of the Buddha's mission

was to deliver beings from suffering by eradicating its cause and to

teach a way to put an end to both birth and death if one wishes to

do so. Incidentally, however, the Buddha has expounded discourses

which tend to worldly progress. Both material and spiritual progress

are essential for the development of a nation. One should not be

separated from the other, nor should material progress be achieved

by sacrificing spiritual progress as is to be witnessed today

amongst materialistic-minded nations in the world. It is the duty of

respective Governments and philanthropic bodies to cater for the

material development of the people and provide congenial conditions,

while religions like Buddhism, in particular, cater for the moral

advancement to make people ideal citizens.

Buddhism goes counter to most

religions in striking the Middle Way and in making its Teaching

homo-centric in contradistinction to theo-centric creeds. As such

Buddhism is introvert and is concerned with individual emancipation.

The Dhamma has to be realized by oneself (sanditthiko).

*

As a rule, the expected ultimate

goal of the majority of mankind is either nihilism or eternalism.

Materialists believe in complete annihilation after death. According

to some religions the goal is to be achieved in an after-life, in

eternal union either with an Almighty Being or an inexplicable force

which, in other words, is one form of eternalism.

*

Buddhism advocates the middle path.

Its goal is neither nihilism, for there is nothing permanent to

annihilate nor eternalism, for there is no permanent soul to

eternalize. The Buddhist goal can be achieved in this life itself.

*

What happens to the Arahant after

death? This is a subtle and difficult question to be answered as

Nibbāna is a supramundane state that cannot be expressed by words

and is beyond space and time. Strictly speaking, there exists a

Nibbāna but no person to attain Nibbāna. The Buddha says it

is not right to state that an Arahant exists nor does not exist

after death. If, for instance, a fire burns and is extinguished, one

cannot say that it went to any of the four directions. When no more

fuel is added, it ceases to burn. The Buddha cites this illustration

of fire and adds that the question is wrongly put. One may-be

confused. But, it is not surprising.

Here is an appropriate illustration

by a modern scientist. Robert Oppenheimer writes:

"If we ask, for instance, whether

the position of the electron remains the same, we must say 'no'; if

we ask whether the electron's position changes with time, we must

say 'no'; if we ask whether the electron is at rest, we must say

'no'; if we ask whether it is in action, we must say 'no'.

"The Buddha had given such answers

when interrogated as to the condition of man's self after

death, but they are not familiar answers from the tradition of the

17th and 18th century science."

Evidently the learned writer is

referring to the state of an Arahant after death.

What is the use of attaining such a

state? Why should we negate existence? Should we not affirm

existence for life is full of joy?

These are not unexpected questions.

They are the typical questions of persons who either desire to enjoy

life or to work for humanity, facing responsibilities and undergoing

suffering.

To the former, a Buddhist would

say:-- you may if you like, but be not slaves to worldly pleasures

which are fleeting and illusory; whether you like it or not, you

will have to reap what you sow. To the latter a Buddhist might

say:-- by all means work for the weal of humanity and seek pleasure

in altruistic service.

Buddhism offers the goal of Nibbāna

to those who need it, and is not forced on any. "Come and see",

advises the Buddha.

*

Till the ultimate goal is achieved a

Buddhist is expected to lead a noble and useful life.

Buddhism possesses an excellent code

of morals suitable to both advanced and unadvanced types of

individuals. They are:

(a) The five Precepts -- not to

kill, not to steal, not to commit adultery, not to lie, and not to

take intoxicating liquor.

(b) The four Sublime States

(Brahma-Vihāra): Loving-kindness, compassion, appreciative joy and

equanimity.

(c) The ten Transcendental virtues

(Pāramitā):--generosity, morality, renunciation, wisdom, energy,

patience, truthfulness, resolution, loving-kindness, and

equanimity.

(d) The Noble Eightfold Path:

Right understanding, right thoughts, right speech, right action,

right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right

concentration.

Those who aspire to attain

Arahantship at the earliest possible opportunity may contemplate on

the exhortation given to Venerable Rāhula by the Buddha ? namely,

"This body is not mine; this am

I not; this is not my soul"

(N'etam mama, n'eso' hamasmi, na me so attā).

*

It should be humbly stated that this

book is not intended for scholars but students who wish to

understand the life of the Buddha and His fundamental teachings.

The original edition of this book

first appeared in 1942. The second one, a revised and enlarged

edition with many additions and modifications, was published in

Saigon in 1964 with voluntary contributions from my devout

Vietnamese supporters. In the present one, I have added two more

chapters and an appendix with some important Suttas.

It gives me pleasure to state that a

Vietnamese translation of this book by Mr. Pham Kim Khanh (Sunanda)

was also published in Saigon.

In preparing this volume I have made

use of the translations of the Pāli Text Society and several works

written by Buddhists and non-Buddhists. At times I may have merely

echoed their authentic views and even used their appropriate

wording. Wherever possible I have acknowledged the source.

I am extremely grateful to the late

Mr. V. F. Gunaratna who, amidst his multifarious duties as Public

Trustee of Ceylon, very carefully revised and edited the whole

manuscript with utmost precision and great faith. Though an onerous

task, it was a labour of love to him since he was an ideal

practising Buddhist, well versed in the Buddha-Dhamma.

My thanks are due to generous

devotees for their voluntary contributions, to Mrs. Coralie La Brooy

and Miss Ranjani Goonetilleke for correcting the proofs and also to

the Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd. for printing the book with

great care.

NĀRADA.

14th July, 2522 - 1980.

Vajirārāma, Colombo 5.

Sri Lanka.

-ooOoo-

THE BUDDHA

CHAPTER

I

FROM BIRTH TO

RENUNCIATION

"A unique Being, an extraordinary

Man arises in this world for the

benefit of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of

compassion for the world, for the good, benefit, and

happiness of gods and men. Who is this Unique Being? It is

the Tathāgata, the Exalted, Fully Enlightened One."

-- Anguttara Nikāya. Pt. I, XIII P. 22.

Birth

On the full moon

day of May,[1]

in the year 623 B.C.[2]

there was born in the

Lumbini Park

[3]

at

Kapilavatthu,[4]

on the Indian borders of

present

Nepal, a noble

prince who was destined to be the greatest religious teacher of the

world.

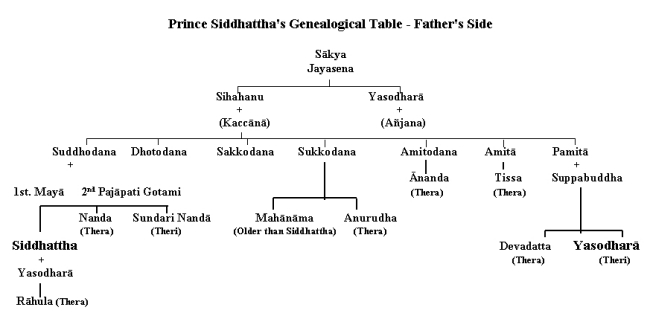

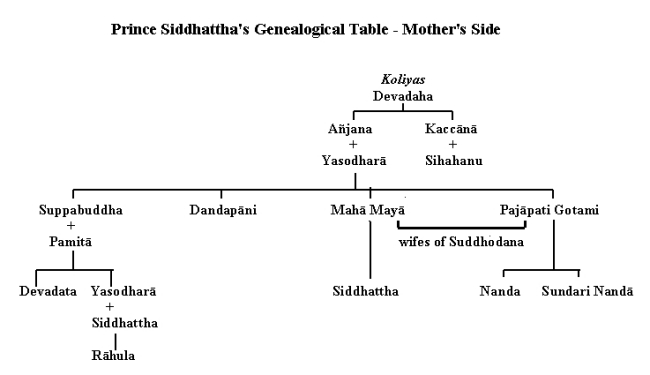

His father[5]

was King Suddhodana of the aristocratic

Sākya

[6]

clan and his mother was Queen

Mahā Māyā. As the beloved mother died seven days after his

birth, Mahā Pajāpati Gotami, her younger sister, who was also

married to the King, adopted the child, entrusting her own son,

Nanda, to the care of the nurses.

Great were the

rejoicings of the people over the birth of this illustrious prince.

An ascetic of high spiritual attainments, named Asita, also

known as Kāladevala, was particularly pleased to hear this

happy news, and being a tutor of the King, visited the palace to see

the Royal babe. The King, who felt honoured by his unexpected visit,

carried the child up to him in order to make the child pay him due

reverence, but, to the surprise of all, the child's legs turned and

rested on the matted locks of the ascetic. Instantly, the ascetic

rose from his seat and, foreseeing with his supernormal vision the

child's future greatness, saluted him with clasped hands.[7]

The Royal father did likewise.

The great ascetic

smiled at first and then was sad. Questioned regarding his mingled

feelings, he answered that he smiled because the prince would

eventually become a Buddha, an Enlightened One, and he was sad

because he would not be able to benefit by the superior wisdom of

the Enlightened One owing to his prior death and rebirth in a

Formless Plane (Arūpaloka).[8]

Naming

Ceremony

On the fifth day

after the prince's birth he was named Siddhattha which means

"wish fulfilled". His family name was Gotama.[9]

In accordance

with the ancient Indian custom many learned brahmins were invited to

the palace for the naming ceremony. Amongst them there were eight

distinguished men. Examining the characteristic marks of the child,

seven of them raised two fingers each, indicative of two alternative

possibilities, and said that he would either become a Universal

Monarch or a Buddha. But the youngest,

Konda[10]

who excelled others in

wisdom, noticing the hair on the forehead turned to the right,

raised only one finger and convincingly declared that the prince

would definitely retire from the world and become a Buddha.

Ploughing

Festival

A very remarkable

incident took place in his childhood. It was an unprecedented

spiritual experience which, later, during his search after truth,

served as a key to his Enlightenment.[11]

To promote

agriculture, the King arranged for a ploughing festival. It was

indeed a festive occasion for all, as both nobles and commoners

decked in their best attire, participated in the ceremony. On the

appointed day, the King, accompanied by his courtiers, went to the

field, taking with him the young prince together with the nurses.

Placing the child on a screened and canopied couch under the cool

shade of a solitary rose-apple tree to be watched by the nurses, the

King participated in the ploughing festival. When the festival was

at its height of gaiety the nurses too stole away from the prince's

presence to catch a glimpse of the wonderful spectacle.

In striking

contrast to the mirth and merriment of the festival it was all calm

and quiet under the rose-apple tree. All the conditions conducive to

quiet meditation being there, the pensive child, young in years but

old in wisdom, sat cross-legged and seized the opportunity to

commence that all-important practice of intent concentration on the

breath -- on exhalations and inhalations -- which gained for him

then and there that one pointedness of mind known as Samādhi

and he thus developed the First

Jhāna

[12]

(Ecstasy). The child's nurses, who had

abandoned their precious charge to enjoy themselves at the festival,

suddenly realizing their duty, hastened to the child and were amazed

to see him sitting cross-legged plunged in deep meditation. The King

hearing of it, hurried to the spot and, seeing the child in

meditative posture, saluted him, saying -- "This, dear child, is my

second obeisance".

Education

As a Royal child,

Prince Siddhattha must have received an education that became

a prince although no details are given about it. As a scion of the

warrior race he received special training in the art of warfare.

Married Life

At the early age

of sixteen, he married his beautiful cousin Princess

Yasodharā

[13]

who was of equal age. For nearly

thirteen years, after his happy marriage, he led a luxurious life,

blissfully ignorant of the vicissitudes of life outside the palace

gates. Of his luxurious life as prince, he states:

"I was

delicate, excessively delicate. In my father's dwelling three

lotus-ponds were made purposely for me. Blue lotuses bloomed in one,

red in another, and white in another. I used no sandal-wood that was

not of Kāsi.[14]

My turban, tunic, dress and cloak, were all from Kāsi.

"Night and day

a white parasol was held over me so that I might not be touched by

heat or cold, dust, leaves or dew.

"There were

three palaces built for me -- one for the cold season, one for the

hot season, and one for the rainy season. During the four rainy

months, I lived in the palace for the rainy season without ever

coming down from it, entertained all the while by female musicians.

Just as, in the houses of others, food from the husks of rice

together with sour gruel is given to the slaves and workmen, even

so, in my father's dwelling, food with rice and meat was given to

the slaves and workmen.[15]"

With the march of

time, truth gradually dawned upon him. His contemplative nature and

boundless compassion did not permit him to spend his time in the

mere enjoyment of the fleeting pleasures of the Royal palace. He

knew no personal grief but he felt a deep pity for suffering

humanity. Amidst comfort and prosperity, he realized the

universality of sorrow.

Renunciation

Prince

Siddhattha reflected thus:

"Why do I,

being subject to birth, decay, disease, death, sorrow and

impurities, thus search after things of like nature. How, if I, who

am subject to things of such nature, realize their disadvantages and

seek after the unattained, unsurpassed, perfect security which is

Nibbāna![16]"

"Cramped and confined is household life, a den of dust, but the life

of the homeless one is as the open air of heaven! Hard is it for him

who bides at home to live out as it should be lived the Holy Life in

all its perfection, in all its purity.[17]"

One glorious day

as he went out of the palace to the pleasure park to see the world

outside, he came in direct contact with the stark realities of life.

Within the narrow confines of the palace he saw only the rosy side

of life, but the dark side, the common lot of mankind, was purposely

veiled from him. What was mentally conceived, he, for the first

time, vividly saw in reality. On his way to the park his observant

eyes met the strange sights of a decrepit old man, a diseased

person, a corpse and a dignified hermit.[18]

The first three sights convincingly proved to him, the inexorable

nature of life, and the universal ailment of humanity. The fourth

signified the means to overcome the ills of life and to attain calm

and peace. These four unexpected sights served to increase the urge

in him to loathe and renounce the world.

Realizing the

worthlessness of sensual pleasures, so highly prized by the

worldling, and appreciating the value of renunciation in which the

wise seek delight, he decided to leave the world in search of Truth

and Eternal Peace.

When this final

decision was taken after much deliberation, the news of the birth of

a son was conveyed to him while he was about to leave the park.

Contrary to expectations, he was not overjoyed, but regarded his

first and only offspring as an impediment. An ordinary father would

have welcomed the joyful tidings, but Prince Siddhattha, the

extraordinary father as he was, exclaimed --"An impediment (rāhu)

has been born; a fetter has arisen". The infant son was

accordingly named Rāhula

[19] by his

grandfather.

The palace was no

longer a congenial place to the contemplative Prince Siddhattha.

Neither his charming young wife nor his lovable infant son could

deter him from altering the decision he had taken to renounce the

world. He was destined to play an infinitely more important and

beneficial role than a dutiful husband and father or even as a king

of kings. The allurements of the palace were no more cherished

objects of delight to him. Time was ripe to depart.

He ordered his

favourite charioteer Channa to saddle the horse Kanthaka,

and went to the suite of apartments occupied by the princess.

Opening the door of the chamber, he stood on the threshold and cast

his dispassionate glance on the wife and child who were fast asleep.

Great was his

compassion for the two dear ones at this parting moment. Greater was

his compassion for suffering humanity. He was not worried about the

future worldly happiness and comfort of the mother and child as they

had everything in abundance and were well protected. It was not that

he loved them the less, but he loved humanity more.

Leaving all

behind, he stole away with a light heart from the palace at

midnight, and rode into the dark, attended only by his loyal

charioteer. Alone and penniless he set out in search of Truth and

Peace. Thus did he renounce the world. It was not the renunciation

of an old man who has had his fill of worldly life. It was not the

renunciation of a poor man who had nothing to leave behind. It was

the renunciation of a prince in the full bloom of youth and in the

plenitude of wealth and prosperity -- a renunciation unparalleled in

history. It was in his twenty-ninth year that Prince Siddhattha

made this historic journey.

He journeyed far

and, crossing the river Anomā, rested on its banks. Here he

shaved his hair and beard and handing over his garments and

ornaments to Channa with instructions to return to the

palace, assumed the simple yellow garb of an ascetic and led a life

of voluntary poverty.

The ascetic

Siddhattha, who once lived in the lap of luxury, now became a

penniless wanderer, living on what little the charitably-minded gave

of their own accord.

He had no

permanent abode. A shady tree or a lonely cave sheltered him by day

or night. Bare-footed and bare-headed, he walked in the scorching

sun and in the piercing cold. With no possessions to call his own,

but a bowl to collect his food and robes just sufficient to cover

the body, he concentrated all his energies on the quest of Truth.

Search

Thus as a

wanderer, a seeker after what is good, searching for the unsurpassed

Peace, he approached Ālāra Kālāma, a distinguished ascetic,

and said: "I desire, friend Kālāma to lead the Holy Life in

this Dispensation of yours."

Thereupon

Ālāra Kālāma told him: "You may stay with me, 0 Venerable One.

Of such sort is this teaching that an intelligent man before long

may realize by his own intuitive wisdom his master's doctrine, and

abide in the attainment thereof."

Before long, he

learnt his doctrine, but it brought him no realization of the

highest Truth.

Then there came

to him the thought: When Ālāra Kalāma declared:

"Having myself

realized by intuitive knowledge the doctrine, I -- 'abide in the

attainment thereof --' it could not have been a mere profession of

faith; surely Ālāra Kālāma lives having understood and

perceived this doctrine."

So he went to him

and said "How far, friend Kālāma, does this doctrine extend

which you yourself have with intuitive wisdom realized and

attained?"

Upon this

Ālāra Kālāma made known to him the Realm of Nothingness

(Āki57;yatana),[20]

an advanced stage of

Concentration.

Then it occurred

to him: "Not only in Ālāra Kālāma are to be found

faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom. I too possess

these virtues. How now if I strive to realize that doctrine whereof

Ālāra Kālāma says that he himself has realized and abides in

the attainment thereof!"

So, before long,

he realized by his own intuitive wisdom that doctrine and attained

to that state, but it brought him no realization of the highest

Truth.

Then he

approached Ālāra Kālāma and said: "Is this the full extent,

friend Kālāma, of this doctrine of which you say that you

yourself have realized by your wisdom and abide in the attainment

thereof?"

"But I also,

friend, have realized thus far in this doctrine, and abide in the

attainment thereof."

The unenvious

teacher was delighted to hear of the success of his distinguished

pupil. He honoured him by placing him on a perfect level with

himself and admiringly said:

"Happy, friend,

are we, extremely happy; in that we look upon such a venerable

fellow-ascetic like you! That same doctrine which I myself have

realized by my wisdom and proclaim, having attained thereunto, have

you yourself realized by your wisdom and abide in the attainment

thereof; and that doctrine you yourself have realized by your wisdom

and abide in the attainment thereof, that have I myself realized by

my wisdom and proclaim, having attained thereunto. Thus the doctrine

which I know, and also do you know; and, the doctrine which you

know, that I know also. As I am, so are you; as you are, so am I.

Come, friend, let both of us lead the company of ascetics."

The ascetic

Gotama was not satisfied with a discipline and a doctrine which

only led to a high degree of mental concentration, but did not lead

to "disgust, detachment, cessation (of suffering), tranquillity;

intuition, enlighten-ment, and Nibbāna." Nor was he anxious to lead

a company of ascetics even with the co-operation of another generous

teacher of equal spiritual attainment, without first perfecting

himself. It was, he felt, a case of the blind leading the blind.

Dissatisfied with his teaching, he politely took his leave from him.

In those happy

days when there were no political disturbances the intellectuals of

India were preoccupied with the study and exposition of some

religious system or other. All facilities were provided for those

more spiritually inclined to lead holy lives in solitude in

accordance with their temperaments and most of these teachers had

large followings of disciples. So it was not difficult for the

ascetic Gotama to find another religious teacher who was more

competent than the former.

On this occasion

he approached one Uddaka Rāmaputta and expressed his

desire to lead the Holy Life in his Dispensation. He was readily

admitted as a pupil.

Before long the

intelligent ascetic Gotama mastered his doctrine and attained

the final stage of mental concentration, the Realm of Neither

Perception nor Non-Perception ("N'eva sa257;

N'asa257;yatana),[21]

revealed by his teacher.

This was the highest stage in worldly concentration when

consciousness becomes so subtle and refined that it cannot be said

that a consciousness either exists or not. Ancient Indian sages

could not proceed further in spiritual development.

The noble teacher

was delighted to hear of the success of his illustrious royal pupil.

Unlike his former teacher the present one honoured him by inviting

him to take full charge of all the disciples as their teacher. He

said: "Happy friend, are we; yea, extremely happy, in that we see

such a venerable fellow-ascetic as you! The doctrine which Rāma

knew, you know; the doctrine which you know, Rāma knew.

As was Rāma so are you; as you are, so was Rāma. Come,

friend, henceforth you shall lead this company of ascetics."

Still he felt

that his quest of the highest Truth was not achieved. He had gained

complete mastery of his mind, but his ultimate goal was far ahead.

He was seeking for the Highest, the Nibbāna, the complete cessation

of suffering, the total eradication of all forms of craving.

"Dissatisfied with this doctrine too, he departed thence, content

therewith no longer."

He realized that

his spiritual aspirations were far higher than those under whom he

chose to learn. He realized that there was none capable enough to

teach him what he yearned for -- the highest Truth. He also realized

that the highest Truth is to be found within oneself and ceased to

seek external aid.

CHAPTER 2

HIS STRUGGLE FOR ENLIGHTENMENT

"Easy

to do are things that are bad and

not beneficial to self,

But very, very hard to do indeed is that which is

beneficial and good".

-- DHAMMAPADA

Struggle

Meeting with disappointment, but not

discouraged, the ascetic Gotama seeking for the incomparable

Peace, the highest Truth, wandered through the district of Magadha,

and arrived in due course at Uruvelā, the market town of

Senāni. There he spied a lovely spot of ground, a charming

forest grove, a flowing river with pleasant sandy fords, and hard by

was a village where he could obtain his food. Then he thought thus:

"Lovely, indeed, O Venerable One, is this spot

of ground, charming is the forest grove, pleasant is the flowing

river with sandy fords, and hard by is the village where I could

obtain food. Suitable indeed is this place for spiritual exertion

for those noble scions who desire to strive."

(Majjhima Nikāya, Ariya-Pariyesana

Sutta No. 26, Vol. 1, p. 16)

The place was congenial for his meditation.

The atmosphere was peaceful. The surroundings were pleasant. The

scenery was charming. Alone, he resolved to settle down there to

achieve his desired object.

Hearing of his renunciation, Konda

the youngest brahmin who predicted his future, and four sons of the

other sages -- Bhaddiya, Vappa, Mahānāma, and

Assaji -- also renounced the world and joined his company.

In the ancient days in India, great importance

was attached to rites, ceremonies, penances and sacrifices. It was

then a popular belief that no Deliverance could be gained unless one

leads a life of strict asceticism. Accordingly, for six long years

the ascetic Gotama made a superhuman struggle practising all

forms of severest austerity. His delicate body was reduced to almost

a skeleton. The more he tormented his body the farther his goal

receded from him.

How strenuously he struggled, the various

methods he employed, and how he eventually succeeded are graphically

described in his own words in various Suttas.

Mahā Saccaka Sutta

[1]

describes his preliminary efforts thus:

"Then the following thought occurred to me:

"How if I were to clench my teeth, press my

tongue against the palate, and with (moral) thoughts hold down,

subdue and destroy my (immoral) thoughts!

"So I clenched my teeth, pressed my tongue

against the palate and strove to hold down, subdue, destroy my

(immoral) thoughts with (moral) thoughts. As I struggled thus,

perspiration streamed forth from my armpits.

"Like unto a strong man who might seize a

weaker man by head or shoulders and hold him down, force him down,

and bring into subjection, even so did I struggle.

"Strenuous and indomitable was my energy. My

mindfulness was established and unperturbed. My body was, however,

fatigued and was not calmed as a result of that painful endeavour --

being overpowered by exertion. Even though such painful sensations

arose in me, they did not at all affect my mind.

"Then I thought thus: How if I were to

cultivate the non-breathing ecstasy!

"Accordingly, I checked inhalation and

exhalation from my mouth and nostrils. As I checked inhalation and

exhalation from mouth and nostrils, the air issuing from my ears

created an exceedingly great noise. Just as a blacksmith's bellows

being blown make an exceedingly great noise, even so was the noise

created by the air issuing from my ears when I stopped breathing.

"Nevertheless, my energy was strenuous and

indomitable. Established and unperturbed was my mindfulness. Yet my

body was fatigued and was not calmed as a result of that painful

endeavour -- being over-powered by exertion.

Even though such painful sensations arose in

me, they did not at all affect my mind.

"Then I thought to myself: 'How if I were to

cultivate that non-breathing exercise!

"Accordingly, I checked inhalation and

exhalation from mouth, nostrils, and ears. And as I stopped

breathing from mouth, nostrils and ears, the (imprisoned) airs beat

upon my skull with great violence. Just as if a strong man were to

bore one's skull with a sharp drill, even so did the airs beat my

skull with great violence as I stopped breathing. Even though such

painful sensations arose in me, they did not at all affect my mind.

"Then I thought to myself: How if I were to

cultivate that non-breathing ecstasy again!

"Accordingly, I checked inhalation and

exhalation from mouth, nostrils, and ears. And as I stopped

breathing thus, terrible pains arose in my head. As would be the

pains if a strong man were to bind one's head tightly with a hard

leathern thong, even so were the terrible pains that arose in my

head. "Nevertheless, my energy was strenuous. Such painful

sensations did not affect my mind.

"Then I

thought to myself: How if I were to cultivate that non-breathing

ecstasy again!

"Accordingly, I stopped breathing from mouth,

nostrils, and ears. As I checked breathing thus, plentiful airs

pierced my belly. Just as if a skilful butcher or a butcher's

apprentice were to rip up the belly with a sharp butcher's knife,

even so plentiful airs pierced my belly.

"Nevertheless, my energy was strenuous. Such

painful sensations did not affect my mind.

"Again I thought to myself: How if I were to

cultivate that non-breathing ecstasy again!

"Accordingly, I checked inhalation and

exhalation from mouth, nostrils, and ears. As I suppressed my

breathing thus, a tremendous burning pervaded my body. Just as if

two strong men were each to seize a weaker man by his arms and

scorch and thoroughly burn him in a pit of glowing charcoal, even so

did a severe burning pervade my body.

"Nevertheless, my energy was strenuous. Such

painful sensations did not affect my mind.

"Thereupon the deities who saw me thus said:

'The ascetic Gotama is dead.' Some remarked: 'The ascetic Gotama is

not dead yet, but is dying'. While some others said: 'The ascetic

Gotama is neither dead nor is dying but an Arahant is the ascetic

Gotama. Such is the way in which an Arahant abides."

Change of Method: Abstinence from Food

"Then I thought to myself: How if I were to

practise complete abstinence from food!

"Then deities approached me and said: 'Do not,

good sir, practise total abstinence from food. If you do practise

it, we will pour celestial essence through your body's pores; with

that you will be sustained."

"And I thought: 'If I claim to be practising

starvation, and if these deities pour celestial essence through my

body's pores and I am sustained thereby, it would be a fraud on my

part.' So I refused them, saying 'There is no need'.

"Then the following thought occurred to me:

How if I take food little by little, a small quantity of the juice

of green gram, or vetch, or lentils, or peas!

"As I took such small quantity of solid and

liquid food, my body became extremely emaciated. Just as are the

joints of knot-grasses or bulrushes, even so were the major and

minor parts of my body owing to lack of food. Just as is the camel's

hoof, even so were my hips for want of food. Just as is a string of

beads, even so did my backbone stand out and bend in, for lack of

food. Just as the rafters of a dilapidated hall fall this way and

that, even so appeared my ribs through lack of sustenance. Just as

in a deep well may be seen stars sunk deep in the water, even so did

my eye-balls appear deep sunk in their sockets, being devoid of

food. Just as a bitter pumpkin, when cut while raw, will by wind and

sun get shrivelled and withered, even so did the skin of my head get

shrivelled and withered, due to lack of sustenance.

"And I, intending to touch my belly's skin,

would instead seize my backbone. When I intended to touch my

backbone, I would seize my belly's skin. So was I that, owing to

lack of sufficient food, my belly's skin clung to the backbone, and

I, on going to pass excreta or urine, would in that very spot

stumble and fall down, for want of food. And I stroked my limbs in

order to revive my body. Lo, as I did so, the rotten roots of my

body's hairs fell from my body owing to lack of sustenance. The

people who saw me said: 'The ascetic Gotama is black.' Some

said, 'The ascetic Gotama is not black but blue.' Some others

said: 'The ascetic Gotama is neither black nor blue but

tawny.' To such an extent was the pure colour of my skin impaired

owing to lack of food.

"Then the following thought occurred to me:

Whatsoever ascetics or brahmins of the past have experienced acute,

painful, sharp and piercing sensations, they must have experienced

them to such a high degree as this and not beyond. Whatsoever

ascetics and brahmins of the future will experience acute, painful,

sharp and piercing sensations they too will experience them to such

a high degree and not beyond. Yet by all these bitter and difficult

austerities I shall not attain to excellence, worthy of supreme

knowledge and insight, transcending those of human states. Might

there be another path for Enlightenment!"

Temptation of Māra the Evil One

His prolonged painful austerities proved

utterly futile. They only resulted in the exhaustion of his valuable

energy. Though physically a superman his delicately nurtured body

could not possibly stand the great strain. His graceful form

completely faded almost beyond recognition. His golden coloured skin

turned pale, his blood dried up, his sinews and muscles shrivelled

up, his eyes were sunk and blurred. To all appearance he was a

living skeleton. He was almost on the verge of death.

At this critical stage, while he was still

intent on the Highest (Padhāna), abiding on the banks of the

Neraā river, striving and contemplating in order to attain

to that state of Perfect Security, came Namuci,[2]

uttering kind words thus:[3]

"'You are lean and deformed. Near to you is

death.

"A thousand parts (of you belong) to death; to

life (there remains) but one. Live, 0 good sir! Life is better.

Living, you could perform merit.

"By leading a life of celibacy and making fire

sacrifices, much merit could be acquired. What will you do with this

striving? Hard is the path of striving, difficult and not easily

accomplished."

Māra reciting these words stood in the

presence of the Exalted One.

To Māra who spoke thus, the Exalted One

replied:

"O Evil One, kinsman of the heedless! You

have come here for your own sake.

"Even an iota of merit is of no avail. To them

who are in need of merit it behoves you, Māra, to speak thus.

"Confidence (Saddhā), self-control (Tapo),[4]

perseverance (Viriya), and wisdom (Pa257;) are mine.

Me who am thus intent, why do you question about life?

"Even the streams of rivers will this wind dry

up. Why should not the blood of me who am thus striving dry up?

"When blood dries up, the bile and phlegm also

dry up. When my flesh wastes away, more and more does my mind get

clarified. Still more do my mindfulness, wisdom, and concentration

become firm.

"While I live thus, experiencing the utmost

pain, my mind does not long for lust! Behold the purity of a being!

"Sense-desires (Kāmā), are your first

army. The second is called Aversion for the Holy Life (Arati).

The third is Hunger and Thirst[5]

(Khuppīpāsā). The fourth is called Craving (Tanhā).

The fifth is Sloth and Torpor (Thina-Middha). The sixth is

called Fear (Bhiru). The seventh is Doubt[6]

(Vicikicchā), and the eighth is Detraction and Obstinacy (Makkha-Thambha).

The ninth is Gain (Lobha), Praise (Siloka) and

Honour (Sakkāra), and that ill-gotten Fame (Yasa). The

tenth is the extolling of oneself and contempt for others (Attukkamsanaparavambhana).

"This, Namuci, is your army, the opposing host

of the Evil One. That army the coward does not overcome, but he who

overcomes obtains happiness.

"This Mu

[7] do I display! What boots life in this world!

Better for me is death in the battle than that one should live on,

vanquished!

[8]

"Some ascetics and brahmins are not seen

plunged in this battle. They know not nor do they tread the path of

the virtuous.

"Seeing the army on all sides with Māra

arrayed on elephant, I go forward to battle. Māra shall not drive me

from my position. That army of yours, which the world together with

gods conquers not, by my wisdom I go to destroy as I would an

unbaked bowl with a stone.

"Controlling my thoughts, and with mindfulness

well-established, I shall wander from country to country, training

many a disciple.

"Diligent, intent, and practising my teaching,

they, disregarding you, will go where having gone they grieve not."

The Middle Path

The ascetic Gotama was now fully

convinced from personal experience of the utter futility of

self-mortification which, though considered indispensable for

Deliverance by the ascetic philosophers of the day, actually

weakened one's intellect, and resulted in lassitude of spirit. He

abandoned for ever this painful extreme as did he the other extreme

of self-indulgence which tends to retard moral progress. He

conceived the idea of adopting the Golden Mean which later became

one of the salient features of his teaching.

He recalled how when his father was engaged in

ploughing, he sat in the cool shade of the rose-apple tree, absorbed

in the contemplation of his own breath, which resulted in the

attainment of the First Jhāna (Ecstasy)[9].

Thereupon he thought: "Well, this is the path to Enlightenment."

He realized that Enlightenment could not be

gained with such an utterly exhausted body: Physical fitness was

essential for spiritual progress. So he decided to nourish the body

sparingly and took some coarse food both hard and soft.

The five favourite disciples who were

attending on him with great hopes thinking that whatever truth the

ascetic Gotama would comprehend, that would he impart to

them, felt disappointed at this unexpected change of method. and

leaving him and the place too, went to Isipatana, saying that "the

ascetic Gotama had become luxurious, had ceased from

striving, and had returned to a life of comfort."

At a crucial time when help was most welcome

his companions deserted him leaving him alone. He was not

discouraged, but their voluntary separation was advantageous to him

though their presence during his great struggle was helpful to him.

Alone, in sylvan solitudes, great men often realize deep truths and

solve intricate problems.

Dawn of Truth

Regaining his lost strength with some coarse

food, he easily developed the First Jhāna which he gained in

his youth. By degrees he developed the second, third and fourth

Jhānas as well.

By developing the Jhānas he gained

perfect one-pointedness of the mind. His mind was now like a

polished mirror where everything is reflected in its true

perspective.

Thus with thoughts tranquillized, purified,

cleansed, free from lust and impurity, pliable, alert, steady, and

unshakable, he directed his mind to the knowledge as regards "The

Reminiscence of Past Births" (Pubbe-nivāsānussati māna).

He recalled his varied lots in former

existences as follows: first one life, then two lives, then three,

four, five, ten, twenty, up to fifty lives; then a hundred, a

thousand, a hundred thousand; then the dissolution of many world

cycles, then the evolution of many world cycles, then both the

dissolution and evolution of many world cycles. In that place he was

of such a name, such a family, such a caste, such a dietary, such

the pleasure and pain he experienced, such his life's end. Departing

from there, he came into existence elsewhere. Then such was his

name, such his family, such his caste, such his dietary, such the

pleasure and pain he did experience, such life's end. Thence

departing, he came into existence here.

Thus he recalled the mode and details of his

varied lots in his former births.

This, indeed, as the First Knowledge that

he realized in the first watch of

the night.

Dispelling thus the ignorance with regard to

the past, he directed his purified mind to "The Perception of the

Disappearing and Reappearing of Beings" (Cutūpapāta māna).

With clairvoyant vision, purified and supernormal, he perceived

beings disappearing from one state of existence and reappearing in

another; he beheld the base and the noble, the beautiful and the

ugly, the happy and the miserable, all passing according to their

deeds. He knew that these good individuals, by evil deeds, words,

and thoughts, by reviling the Noble Ones, by being misbelievers, and

by conforming themselves to the actions of the misbelievers, after

the dissolution of their bodies and after death, had been born in

sorrowful states. He knew that these good individuals, by good

deeds, words, and thoughts, by not reviling the Noble Ones, by being

right believers, and by conforming themselves to the actions of the

right believers, after the dissolution of their bodies and after

death, had been born in happy celestial worlds.

Thus with clairvoyant supernormal vision he

beheld the disappearing and the reappearing of beings.

This, indeed, was the Second Knowledge that

he realized in the middle watch of the night.

Dispelling thus the ignorance with regard to

the future, he directed his purified mind to "The Comprehension of

the Cessation of Corruptions"

[10] (Āsavakkhaya māna).

He realized in accordance with fact: "This is

Sorrow", "This, the Arising of Sorrow", "This, the Cessation of

Sorrow", "This, the Path leading to the Cessation of Sorrow".

Likewise in accordance with fact he realized: "These are the

Corruptions", "This, the Arising of Corruptions", "This, the

Cessation of Corruptions", "This, the Path leading to the Cessation

of Corruptions". Thus cognizing, thus perceiving, his mind was

delivered from the Corruption of Sensual Craving; from the

Corruption of Craving for Existence; from the Corruption of

Ignorance.

Being delivered, He knew, "Delivered am I

[11] and He realized, "Rebirth is ended;

fulfilled the Holy Life; done what was to be done; there is

no more of this state again.[12]"

This was the Third Knowledge that He

Realized in the last watch of the

night.

Ignorance was dispelled, and wisdom arose;

darkness vanished, and light arose.

CHAPTER

3

THE BUDDHAHOOD

"The

Tathāgatas are only teachers".

-- DHAMMAPADA

Characteristics of the Buddha

After a

stupendous struggle of six strenuous years, in His 35th year the

ascetic Gotama, unaided and unguided by any supernatural

agency, and solely relying on His own efforts and wisdom, eradicated

all defilements, ended the process of grasping, and, realizing

things as they truly are by His own intuitive knowledge, became a

Buddha -- an Enlightened or Awakened One.

Thereafter he was known as Buddha Gotama,[1]

one of a long series of Buddhas that appeared in the past and will

appear in the future.

He was

not born a Buddha, but became a Buddha by His own efforts.

The Pāli

term Buddha is derived from "budh", to understand, or to be

awakened. As He fully comprehended the four Noble Truths and as He

arose from the slumbers of ignorance He is called a Buddha. Since He

not only comprehends but also expounds the doctrine and enlightens

others, He is called a Sammā Sambuddha -- a Fully Enlightened

One -- to distinguish Him from Pacceka (Individual) Buddhas

who only comprehend the doctrine but are incapable of enlightening

others.

Before

His Enlightenment He was called Bodhisatta[2]

which means one who is aspiring to attain Buddhahood.

Every

aspirant to Buddhahood passes through the Bodhisatta Period -- a

period of intensive exercise and development of the qualities of

generosity, discipline, renunciation, wisdom, energy, endurance,

truthfulness, determination, benevolence and perfect equanimity.

In a

particular era there arises only one Sammā Sambuddha. Just as

certain plants and trees can bear only one flower even so one

world-system (lokadhātu) can bear only one Sammā Sambuddha.

The

Buddha was a unique being. Such a being arises but rarely in this

world, and is born out of compassion for the world, for the good,

benefit, and happiness of gods and men. The Buddha is called "acchariya

manussa" as He was a wonderful man. He is called "amatassa

dātā" as He is the giver of Deathlessness. He is called "varado"

as He is the Giver of the purest love, the profoundest wisdom,

and the Highest Truth. He is also called Dhammassāmi as He is

the Lord of the Dhamma (Doctrine).

As the

Buddha Himself says, "He is the Accomplished One (Tathāgata),

the Worthy One (Araham), the Fully Enlightened One (Sammā

Sambuddha), the creator of the unarisen way, the producer of the

unproduced way, the proclaimer of the unproclaimed way, the knower

of the way, the beholder of the way, the cognizer of the way."[3]

The

Buddha had no teacher for His Enlightenment. "Na me ācariyo atthi"

[4] -- A teacher have I not -- are His own

words. He did receive His mundane knowledge from His lay teachers,[5]

but teachers He had none for His supramundane knowledge which He

himself realized by His own intuitive wisdom.

If He had

received His knowledge from another teacher or from another

religious system such as Hinduism in which He was nurtured, He could

not have said of Himself as being the incomparable teacher (aham

satthā anuttaro).[6]

In His first discourse He declared that light arose in things

not heard before.

During

the early period of His renunciation He sought the advice of the

distinguished religious teachers of the day, but He could not find

what He sought in their teachings. Circumstances compelled Him to

think for Himself and seek the Truth. He sought the Truth within

Himself. He plunged into the deepest profundities of thought, and He

realized the ultimate Truth which He had not heard or known before.

Illumination came from within and shed light on things which He had

never seen before.

As He

knew everything that ought to be known and as He obtained the key to

all knowledge, He is called Sabbannū --the Omniscient

One. This supernormal knowledge He acquired by His own efforts

continued through a countless series of births.

Who

is the Buddha?

Once a

certain brahmin named Dona, noticing the characteristic marks

of the footprint of the Buddha, approached Him and questioned Him.

"Your

Reverence will be a Deva?[7]"

"No,

indeed, brahmin, a Deva am I not," replied the Buddha.

"Then

Your Reverence will be a Gandhabba?

[8]"'

"No,

indeed, brahmin, a Gandhabba am I not."

"A Yakkha

then?[9]"

"No,

indeed, brahmin, not a Yakkha."

"Then

Your Reverence will be a human being?"

"No,

indeed, brahmin, a human being am I not."

"Who,

then, pray, will Your Reverence be?"

The

Buddha replied that He had destroyed Defilements which condition

rebirth as a Deva, Gandhabba, Yakkha, or a human being and added:

"As a

lotus, fair and lovely,

By the water is not soiled,

By the world am I not soiled;

Therefore, brahmin, am I Buddha.[10]"'

The

Buddha does not claim to be an incarnation (Avatāra) of Hindu

God Vishnu, who, as the Bhagavadgitā[11]

charmingly sings, is born again and again in different periods to

protect the righteous, to destroy the wicked, and to establish the

Dharma (right).

According

to the Buddha countless are the gods (Devas) who are also a

class of beings subject to birth and death; but there is no one

Supreme God, who controls the destinies of human beings and who

possesses a divine power to appear on earth at different intervals,

employing a human form as a vehicle[12].

Nor does

the Buddha call Himself a "Saviour" who freely saves others by his

personal salvation. The Buddha exhorts His followers to depend on

themselves for their deliverance, since both defilement and purity

depend on oneself. One cannot directly purify or defile another.[13]

Clarifying His relationship with His followers and emphasizing the

importance of self-reliance and individual striving, the Buddha

plainly states:

"You

yourselves should make an exertion. The Tathāgatas are only

teachers.[14]"'

The

Buddha only indicates the path and method whereby He delivered

Himself from suffering and death and achieved His ultimate goal. It

is left for His faithful adherents who wish their release from the

ills of life to follow the path.

"To

depend on others for salvation is negative, but to depend on oneself

is positive." Dependence on others means a surrender of one's

effort.

"Be ye

isles unto yourselves; be ye a refuge unto yourselves; seek no

refuge in others.[15]"

These

significant words uttered by the Buddha in His last days are very

striking and inspiring. They reveal how vital is self-exertion to

accomplish one's ends, and how superficial and futile it is to seek

redemption through benignant saviours, and crave for illusory

happiness in an afterlife through the propitiation of imaginary gods

by fruitless prayers and meaningless sacrifices.

The

Buddha was a human being. As a man He was born, as a Buddha He

lived, and as a Buddha His life came to an end. Though human, He

became an extraordinary man owing to His unique characteristics. The

Buddha laid stress on this important point, and left no room for any

one to fall into the error of thinking that He was an immortal

being. It has been said of Him that there was no religious teacher

who was "ever so godless as the Buddha, yet none was so god-like.[16]"

In His own time the Buddha was no doubt highly venerated by His

followers, but He never arrogated to Himself any divinity.

The

Buddha's Greatness

Born a

man, living as a mortal, by His own exertion He attained that

supreme state of perfection called Buddhahood, and without keeping

His Enlightenment to Himself, He proclaimed to the world the latent

possibilities and the invincible power of the human mind. Instead of

placing an unseen Almighty God over man, and giving man a

subservient position in relation to such a conception of divine

power, He demonstrated how man could attain the highest knowledge

and Supreme Enlightenment by his own efforts. He thus raised the

worth of man. He taught that man can gain his deliverance from the

ills of life and realize the eternal bliss of Nibbāna without

depending on an external God or mediating priests. He taught the

egocentric, power-seeking world the noble ideal of selfless service.

He protested against the evils of caste-system that hampered the

progress of mankind and advocated equal opportunities for all. He

declared that the gates of deliverance were open to all, in every

condition of life, high or low, saint or sinner, who would care to

turn a new leaf and aspire to perfection. He raised the status of

down-trodden women, and not only brought them to a realization of

their importance to society but also founded the first religious

order for women. For the first time in the history of the world He

attempted to abolish slavery. He banned the sacrifice of unfortunate

animals and brought them within His compass of loving kindness. He

did not force His followers to be slaves either to His teachings or

to Himself, but granted complete freedom of thought and admonished

His followers to accept His words not merely out of regard for Him

but after subjecting them to a thorough examination "even as the

wise would test gold by burning, cutting, and rubbing it on a piece

of touchstone." He comforted the bereaved mothers like Patācārā and

Kisāgotami by His consoling words. He ministered to the deserted

sick like Putigatta Tissa Thera with His own hands. He helped the

poor and the neglected like Rajjumālā and Sopāka and saved them from

an untimely and tragic death. He ennobled the lives of criminals

like Angulimala and courtesans like Ambapāli. He encouraged the

feeble, united the divided, enlightened the ignorant, clarified the

mystic, guided the deluded, elevated the base, and dignified the

noble. The rich and the poor, the saint and the criminal, loved Him

alike. His noble example was a source of inspiration to all. He was

the most compassionate and tolerant of teachers.

His will,

wisdom, compassion, service, renunciation, perfect purity, exemplary

personal life, the blameless methods that were employed to propagate

the Dhamma and His final success -- all these factors have compelled

about one fifth of the population of the world to hail the Buddha as

the greatest religious teacher that ever lived on earth.

Paying a

glowing tribute to the Buddha, Sri Radhakrishnan writes:

"In

Gautama the Buddha we have a master mind from the East second to

none so far as the influence on the thought and life of the human

race is concerned, and sacred to all as the founder of a religious

tradition whose hold is hardly less wide and deep than any other. He

belongs to the history of the world's thought, to the general

inheritance of all cultivated men, for, judged by intellectual

integrity, moral earnestness, and spiritual insight, he is

undoubtedly one of the greatest figures in history.[17]"

In the

Three Greatest Men in History H. G. Wells states:

"In

the Buddha you see clearly a man, simple, devout, lonely, battling

for light, a vivid human personality, not a myth. He too gave a

message to mankind universal in character. Many of our best modern

ideas are in closest harmony with it. All the miseries and

discontents of life are due, he taught, to selfishness. Before a man

can become serene he must cease to live for his senses or himself.

Then he merges into a greater being. Buddhism in different language

called men to self-forgetfulness 500 years before Christ. In some

ways he was nearer to us and our needs. He was more lucid upon our

individual importance in service than Christ and less ambiguous upon

the question of personal immortality."

The Poet

Tagore calls Him the Greatest Man ever born.

In

admiration of the Buddha, Fausboll, a Danish scholar says -- "The

more I know Him, the more I love Him."

A humble

follower of the Buddha would modestly say: The more I know Him, the

more I love Him; the more I love Him, the more I know Him.

CHAPTER

4

AFTER THE ENLIGHTENMENT

"Happy in

this world is non-attachment".

-- UDĀNA

In the memorable forenoon, immediately preceding the morn

of His Enlightenment, as the Bodhisatta was seated under the

Ajapāla banyan tree in close proximity to the Bodhi tree,[1]

a generous lady, named Sujātā, unexpectedly offered Him

some rich milkrice, specially prepared by her with great care.

This

substantial meal He ate, and after His Enlightenment the Buddha

fasted for seven weeks, and spent a quiet time, in deep

contemplation, under the Bodhi tree and in its neighbourhood.

The Seven Weeks

First Week

Throughout the

first week the Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree in one posture,

experiencing the Bliss of Emancipation (Vimutti Sukha, i.e

The Fruit of Arahantship).

After those

seven days had elapsed, the Buddha emerged from the state of

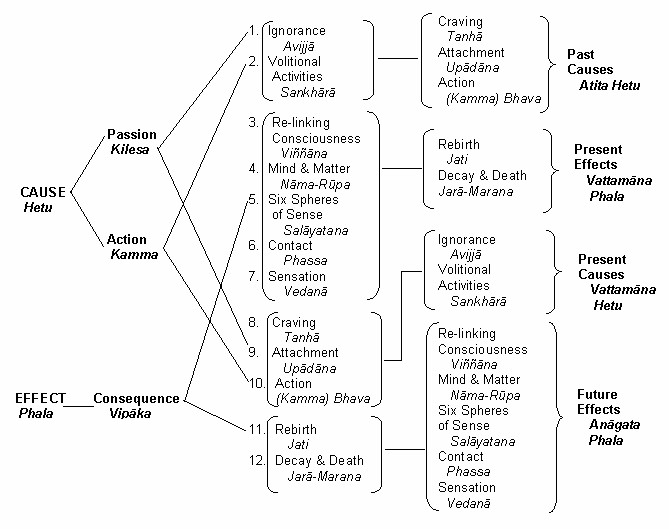

concentration, and in the first watch of the night, thoroughly

reflected on "The Dependent Arising" (Paticca Samuppāda) in

direct order thus: "When this (cause) exists, this (effect) is;

with the arising of this (cause), this effect arises.[2]"

Dependent on

Ignorance (avijjā) arise moral and immoral Conditioning

Activities (samkhārā).

Dependent on Conditioning Activities arises (Relinking)

Consciousness (vi257;na).

Dependent on (Relinking) Consciousness arise Mind and Matter

(nāma-rūpa).

Dependent on Mind and Matter arise the Six Spheres of Sense

(salāyatana).

Dependent on the Six Spheres of Sense arises Contact

(phassa).

Dependent on Contact arises Feeling (vedanā).

Dependent on Feeling arises Craving (tanhā)

Dependent on Craving arises Grasping (upādāna).

Dependent on Grasping arises Becoming (bhava)

Dependent on Becoming arises Birth (jāti)

Dependent on Birth arise Decay (jarā), Death (marana),

Sorrow (soka), Lamentation (parideva), Pain

(dukkha), Grief (domanassa), and Despair (upāyāsa).

Thus does this

whole mass of suffering originate.

Thereupon the

Exalted One, knowing the meaning of this, uttered, at that time,

this paean of joy:

"When, indeed,

the Truths become manifest unto the strenuous, meditative Brahmana[3],

then do all his doubts vanish away, since he knows the truth

together with its cause."

In the middle

watch of the night the Exalted One thoroughly reflected on "The

Dependent Arising" in reverse order thus: "When this cause does

not exist, this effect is not; with the cessation of this cause,

this effect ceases.

With the

cessation of Ignorance, Conditioning Activities cease.

With the cessation of Conditioning Activities (Relinking)

Consciousness ceases.

With the cessation of (Relinking) Consciousness, Mind and Matter

cease.

With the cessation of Mind and Matter, the six Spheres of Sense

cease.

With the cessation of the Six Spheres of Sense, Contact ceases.

With the cessation of Contact, Feeling ceases.

With the cessation of Feeling, Craving ceases.

With the cessation of Craving, Grasping ceases.

With the cessation of Grasping, Becoming ceases.

With the cessation of Becoming, Birth ceases.

With the cessation of Birth, Decay, Death, Sorrow, Lamentation,

Pain, Grief, and Despair cease.

Thus does this

whole mass of suffering cease.

Thereupon the

Exalted One, knowing the meaning of this, uttered, at that time,

this paean of joy:

"When, indeed,

the Truths become manifest unto the strenuous and meditative

Brahmana, then all his doubts vanish away since he has understood

the destruction of the causes."

In the third

watch of the night, the Exalted One reflected on "The Dependent

Arising" in direct and reverse order thus. "When this cause

exists, this effect is; with the arising of this cause, this

effect arises. When this cause does not exist, this effect is not;

with the cessation of this cause, this effect ceases."

Dependent on

Ignorance arise Conditioning Activities .... and so forth.

Thus does this

whole mass of suffering arises.

With the

cessation of Ignorance, Conditioning Activities cease .... and so

forth.

Thus does this

whole mass of suffering ceases.

Thereupon the

Blessed One, knowing the meaning of this, uttered, at that time,

this paean of joy:

"When indeed

the Truths become manifest unto the strenuous and meditative

Brahmana, then he stands routing the hosts of the Evil One even as

the sun illumines the sky."

Second Week

The second week

was uneventful, but He silently taught a great moral lesson to the

world. As a mark of profound gratitude to the inanimate Bodhi tree

that sheltered him during His struggle for Enlightenment, He stood

at a certain distance gazing at the tree with motionless eyes for

one whole week.[4]

Following His

noble example, His followers, in memory of His Enlightenment,

still venerate not only the original Bodbi tree but also its

descendants.[5]

Third week

As the Buddha

had not given up His temporary residence at the Bodhi tree the

Devas doubted His attainment to Buddhahood. The Buddha read their

thoughts, and in order to clear their doubts He created by His

psychic powers a jewelled ambulatory (ratana camkamana) and

paced up and down for another week.

Fourth Week

The fourth week

He spent in a jewelled chamber

(ratanaghara)[6]

contemplating the

intricacies of the Abhidhamma (Higher Teaching). Books state that

His mind and body were so purified when He pondered on the Book of

Relations (Patthāna), the seventh treatise of the

Abhidbamma, that six coloured rays emitted from His body.[7]

Fifth week

During the

fifth week too the Buddha enjoyed the Bliss of Emancipation (Vimuttisukha),

seated in one posture 'under the famous Ajapāla banyan

tree in the vicinity of the Bodhi tree. When He arose from that

transcendental state a conceited (huhunkajātika) brahmin

approached Him and after the customary salutations and friendly

greetings, questioned Him thus: "In what respect, 0 Venerable

Gotama, does one become a Brahmana and what are the conditions

that make a Brahmana?"

The Buddha

uttered this paean of joy in reply:

"That brahmin

who has discarded evil, without conceit (huhumka), free

from Defilements, self-controlled, versed in knowledge and who has

led the Holy Life rightly, would call himself a Brahmana. For him

there is no elation anywhere in this world.[8]"

According to

the Jātaka commentary it was during this week that the daughters

of Māra -- Tanhā, Arati and

Ragā[9]--

made a vain attempt to

tempt the Buddha by their charms.

Sixth week

From the

Ajapāla banyan tree the Buddha proceeded to the Mucalinda

tree, where he spent the sixth week, again enjoying the Bliss

of Emancipation. At that time there arose an unexpected great

shower. Rain clouds and gloomy weather with cold winds prevailed

for several days.

Thereupon

Mucalinda, the serpent-king,[10]

came out of his abode, and coiling round the body of the Buddha

seven times, remained keeping his large hood over the head of the

Buddha so that He may not be affected by the elements.

At the close of

seven days Mucalinda, seeing the clear, cloudless sky,

uncoiled himself from around the body of the Buddha, and, leaving

his own form, took the guise of a young man, and stood in front of

the Exalted One with clasped hands.

Thereupon the

Buddha uttered this paean of joy:

"Happy is

seclusion to him who is contented, to him who has heard the truth,

and to him who sees. Happy is goodwill in this world, and so is

restraint towards all beings. Happy in this world is

non-attachment, the passing beyond of sense desires. The

suppression of the 'I am' conceit is indeed the highest happiness.[11]

Seventh week

The seventh

week the Buddha peacefully passed at the Rājāyatana tree,

experiencing the Bliss of Emancipation.

One of the

First Utterances of the Buddha

Thro' many

a birth in existence wandered I,

Seeking, but not finding, the builder of this

house.

Sorrowful is repeated birth.

O housebuilder,[12]

thou art seen. Thou shall build

no house

[13] again.

All thy rafters

[14] are broken.

Thy ridgepole

[15] is

shattered.

Mind attains the Unconditioned.

[16]

Achieved is the End of Craving.

At dawn on the

very day of His Enlightenment the Buddha uttered this paean of joy

(Udāna) which vividly describes His transcendental moral

victory and His inner spiritual experience.

The Buddha

admits His past wanderings in existence which entailed suffering,

a fact that evidently proves the belief in rebirth. He was

compelled to wander and consequently to suffer, as He could not

discover the architect that built this house, the body. In His

final birth, while engaged in solitary meditation which He had

highly developed in the course of His wanderings, after a

relentless search He discovered by His own intuitive wisdom the

elusive architect, residing not outside but within the recesses of

His own heart. It was craving or attachment, a self-creation, a

mental element latent in all. How and when this craving originated

is incomprehensible. What is created by oneself can be destroyed

by oneself. The discovery of the architect is the eradication of

craving by attaining Arhantship, which in these verses is alluded

to as "end of craving."

The rafters of

this self-created house are the passions (kilesa) such as

attachment (lobha) aversion (dosa), illusion

(moha), conceit (māna), false views (ditthi),

doubt (vicikicchā), sloth (thīna), restlessness (uddhacca),