ARAHATTAMAGGA

ARAHATTAPHALA

The Path to Arahantship

A Compilation of Venerable Ācariya Mahā Boowa’s Dhamma Talks About His Path of Practice

Translated by from the Thai by Bhikkhu Dick Sīlaratano

THIS BOOK IS A GIFT OF DHAMMA & PRINTED ONLY FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION.

The Dhamma should not be sold like goods in the market place. Permission to reproduce in any way for free distribution, as a gift of Dhamma, is hereby granted and no further permission need be obtained. Reproduction in any way for commercial gain is prohibited.

Author: Venerable Ãcariya Mahã Boowa Ñãnasampanno

Translator: Bhikkhu Dick Sïlaratano

1st Printing May, 2005

ISBN: 974-93100-1-2

Printed in Thailand by Silpa Siam Packaging & Printing Co., Ltd.

Tel: (662) 444-3351-9

Any Inquiries can be addressed to:

Forest Dhamma Books

Baan Taad Forest Monastery

Baan Taad, Ampher Meung

Udon Thani, 41000

Thailand

FDBooks@gmail.com

© www.ForestDhammaBooks.com

Part 1. Arahattamagga: The Direct Route to the End of All Suffering

Part 2. Arahattaphala: Shedding Tears in Amazement with Dhamma

Part 3. Arahattapatta: How Can an Arahant Shed Tears?

A FOREST DHAMMA PUBLICATION OF BAAN TAAD FOREST MONASTERY

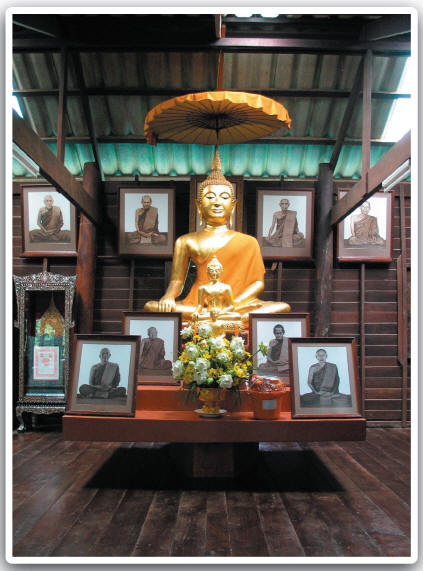

Venerable Ãcariya Mun Bhuridatta Thera

(1870-1949)

Venerable Ãcariya Mahã Boowa Ñãnasampanno Thera

(1913-)

ARAHATTAMAGGA

The Direct Route to the End of All Suffering

A Compilation of Venerable Acariya Maha Boowa's Dhamma Talks

About the Development of His Meditation Practice.

At

present, all that is left of Buddhism are the words of the Buddha. Only his

teachings—the scriptures—remain. Please be aware of this. Due to the

corruption caused by the defiling nature of the kilesas, true spiritual

principles are no longer practiced in present-day Buddhism. As Buddhists, we

constantly allow our minds to be agitated and confused, engulfed in mental

defilements that assail us from every direction. They so overpower our minds

that we never rise above these contaminating influences, no matter how hard

we try. The vast majority of people are not even interested enough to try:

They simply close their eyes and allow the onslaught to overwhelm them. They

don’t even attempt to put up the least amount of resistance. Since they lack

the mindfulness needed to pay attention to the consequences of their

thoughts, all their thinking and all they do and say are instances of the

kilesas giving them a beating. They surrendered to the power of these

ruinous forces such a long time ago that they now lack any motivation to

restrain their wayward thoughts. When mindfulness is absent, the kilesas

work with impunity, day and night, in every sphere of activity. In the

process, they increasingly burden and oppress the hearts and minds of people

everywhere with dukkha.

In the time of the Buddha, his direct disciples were true practitioners

of the way of Buddhism. They renounced the world for the express purpose of

transcending dukkha. Regardless of their social status, age or gender, when

they ordained under the Buddha’s guidance, they changed their habitual ways

of thinking, acting, and speaking to the way of Dhamma. Casting the kilesas

aside, the disciples ceased to follow their lead from that moment on. With

earnest effort, they directed all their energy toward purifying their hearts

and cleansing them of the contamination created by the kilesas.

In essence, earnest effort is synonymous with a meditator’s endeavor to

maintain steady and continuous mindful awareness, always striving to keep a

constant watch on the mind. When mindfulness oversees all our mental and

emotional activities, at all times in all postures, this is called “right

effort”. Whether we’re engaged in formal meditation practice or not, if we

earnestly endeavor to keep our minds firmly focused in the present moment,

we constantly offset the threat posed by the kilesas. The kilesas work

tirelessly to churn out thoughts of the past and the future. This distracts

the mind, drawing it away from the present moment, and from the mindful

awareness that maintains our effort.

For this reason, meditators should not allow their minds to wander into

worldly thoughts about the past or the future. Such thinking is invariably

bound up with the kilesas, and thus, hinders practice. Instead of following

the tendency of the kilesas to focus externally on the affairs of the world

outside, meditators must focus internally and become aware of the mind’s

inner world. This is essential.

Largely because they are not sufficiently resolute in applying basic

principles of meditation, many meditators fail to gain satisfactory results.

I always teach my pupils to be very precise in their pursuit and to have a

clear and specific focus in their meditation. That way they are sure to get

good results. It is important to find a suitable object of attention to

properly prepare the mind for this kind of work. I usually recommend a

preparatory meditation-word whose continuous mental repetition acts as an

anchor that quickly grounds the meditator’s mind in a state of meditative

calm and concentration. If a meditator simply focuses attention on the

presence of awareness in the mind without a meditation-word to anchor him,

the results are bound to be hit and miss. The mind’s knowing presence is too

subtle to give mindfulness a firm basis, so the mind soon strays into

thinking and distraction—lured by the siren call of the kilesas. Meditation

practice then becomes patchy. At certain times it seems to progress

smoothly, almost effortlessly, only to become suddenly and unexpectedly

difficult. It falters, and all apparent progress disappears. With its

confidence shaken, the mind is left floundering. However, if we use a

meditation-word as an anchor to solidly ground our mindfulness, then the

mind is sure to attain a state of meditative calm and concentration in the

shortest possible time. It will also have the means to maintain that calm

state with ease.

I am speaking here from personal experience. When I first began to

meditate, my practice lacked a solid foundation. Since I had yet to discover

the right method to look after my mind, my practice was in a state of

constant flux. It would make steady progress for awhile only to decline

rapidly and fall back to its original untutored condition. Due to the

intense effort I exerted in the beginning, my mind succeeded in attaining a

calm and concentrated state of samadhi. It felt as substantial and stable as

a mountain. Still lacking a suitable method for maintaining this state, I

took it easy and rested on my laurels. That was when my practice suffered a

decline. My practice began to deteriorate, but I didn’t know how to reverse

the decline. So I thought long and hard, trying to find a firm basis on

which I could expect to stabilize my mind. Eventually, I came to the

conclusion that mindfulness had deserted me because my fundamentals were

wrong: I lacked a meditation-word to act as a precise focus for my

attention.

I was forced to begin my practice anew. This time I first drove a stake

firmly into the ground and held tightly to it no matter what happened. That

stake was buddho, the recollection of the Buddha. I made the meditation-word

buddho the sole object of my attention. I focused on the mental repetition

of buddho to the exclusion of everything else. Buddho became my sole

objective even as I made sure that mindfulness was always in control to

direct the effort. All thoughts of progress or decline were put aside. I

would let happen whatever was going to happen. I was determined not to

indulge in my old thought patterns: thinking about the past—when my practice

was progressing nicely—and of how it collapsed; then thinking of the future,

hoping that, somehow, through a strong desire to succeed, my previous sense

of contentment would return on its own. All the while, I had failed to

create the condition that would bring the desired results. I merely wished

to see improvement, only to be disappointed when it failed to materialize.

For, in truth, desire for success does not bring success; only mindful

effort will.

This time I resolved that, no matter what occurred, I should just let

it happen. Fretting about progress and decline was a source of agitation,

distracting me from the present moment and the work at hand. Only the

mindful repetition of buddho could prevent fluctuations in my meditation. It

was paramount that I center the mind on awareness of the immediate present.

Discursive thinking could not be allowed to disrupt concentration.

To practice meditation earnestly to attain an end to all suffering, you

must be totally committed to the work at each successive stage of the path.

Nothing less than total commitment will succeed. To experience the deepest

levels of samadhi and achieve the most profound levels of wisdom, you cannot

afford to be halfhearted and listless, forever wavering because you lack

firm principles to guide your practice. Meditators without a firm commitment

to the principles of practice can meditate their entire lives without

gaining the proper results. In the initial stages of practice, you must find

a stable object of meditation with which to anchor your mind. Don’t just

focus casually on an ambiguous object, like awareness that is always present

as the mind’s intrinsic nature. Without a specific object of attention to

hold your mind, it will be almost impossible to keep your attention from

wandering. This is a recipe for failure. In the end, you’ll become

disappointed and give up trying.

When mindfulness loses its focus, the kilesas rush in to drag your

thoughts to a past long gone, or a future yet to come. The mind becomes

unstable and strays aimlessly over the mental landscape, never remaining

still or contented for a moment. This is how meditators lose ground while

watching their meditation practice collapse. The only antidote is a single,

uncomplicated focal point of attention; such as a meditation-word or the

breath. Choose one that seems most appropriate to you, and focus steadfastly

on that one object to the exclusion of everything else. Total commitment is

essential to the task.

If you choose the breath as your focal point, make yourself fully aware

of each in-breath and each out-breath. Notice the sensation created by the

breath’s movement and fix your attention on the point where that feeling is

most prominent; where the sensation of the breath is felt most acutely: for

example, the tip of the nose. Make sure you know when the breath comes in

and when it goes out, but don’t follow its course—simply focus on the spot

where it passes through. If you find it helpful, combine your breathing with

a silent repetition of buddho, thinking bud on the point of inhalation and

dho on the point of exhalation. Don’t allow errant thoughts to interfere

with the work you are doing. This is an exercise in awareness of the

present-moment; so remain alert and fully attentive.

As mindfulness gradually establishes itself, the mind will stop paying

attention to harmful thoughts and emotions. It will lose interest in its

usual preoccupations. Undistracted, it will settle further and further into

calm and stillness. At the same time, the breath—which is coarse when you

first begin focusing on it—gradually becomes more and more refined. It may

even reach the stage where it completely disappears from your conscious

awareness. It becomes so subtle and refined that it fades and disappears.

There is no breath at that time—only the mind’s essential knowing nature

remains.

MY CHOICE WAS BUDDHO MEDITATION. From the moment I made my resolve, I kept

my mind from straying from the repetition of buddho. From the moment I awoke

in the morning until I slept at night, I forced myself to think only of

buddho. At the same time, I ceased to be preoccupied with thoughts of

progress and decline: If my meditation made progress, it would do so with

buddho; if it declined, it would go down with buddho. In either case, buddho

was my sole preoccupation. All other concerns were irrelevant.

Maintaining such single-minded concentration is not an easy task. I had

to literally force my mind to remain entwined with buddho each and every

moment without interruption. Regardless of whether I was seated in

meditation, walking meditation or simply doing my daily chores, the word

buddho resonated deeply within my mind at all times. By nature and

temperament, I was always extremely resolute and uncompromising. This

tendency worked to my advantage. In the end, I became so earnestly committed

to the task that nothing could shake my resolve; no errant thought could

separate the mind from buddho.

Working at this practice day after day, I always made certain that

buddho resonated in close harmony with my present-moment awareness. Soon, I

began to see the results of calm and concentration arise clearly within the

citta, the mind’s essential knowing nature. At that stage, I began to see

the very subtle and refined nature of the citta. The longer I internalized

buddho, the more subtle the citta became, until eventually the subtlety of

buddho and the subtlety of the citta melded into one another and became one

and the same essence of knowing. I could not separate buddho from the

citta’s subtle nature. Try as I might, I could not make the word buddho

appear in my mind. Through diligence and perseverance, buddho had become so

closely unified with the citta that buddho itself no longer appeared within

my awareness. The mind had become so calm and still, so profoundly subtle,

that nothing, not even buddho, resonated there. This meditative state is

analogous to the disappearance of the breath, as mentioned above.

When this took place, I felt bewildered. I had predicated my whole

practice on holding steadfastly to buddho. Now that buddho was no longer

apparent, where would I focus my attention? Up to this point, buddho had

been my mainstay. Now it had disappeared. No matter how hard I tried to

recover this focus, it was lost. I was in a quandary. All that remained then

was the citta’s profoundly subtle knowing nature, a pure and simple

awareness, bright and clear. There was nothing concrete within that

awareness to latch on to.

I realized then that nothing invades the mind’s sphere of awareness

when consciousness—its knowing presence—reaches such a profound and subtle

condition. I was left with only one choice: With the loss of buddho, I had

to focus my attention on the essential sense of awareness and knowing that

was all-present and prominent at that moment. That consciousness had not

disappeared; on the contrary, it was all-pervasive. All of the mindful

awareness that had concentrated on the repetition of buddho was then firmly

refocused on the very subtle knowing presence of the calm and converged

citta. My attention remained firmly fixed on that subtle knowing essence

until eventually its prominence began to fade, allowing my normal awareness

to become reestablished.

As normal awareness returned, buddho manifested itself once more. So I

immediately refocused my attention on the repetition of my meditation-word.

Before long, my daily practice assumed a new rhythm: I concentrated intently

on buddho until consciousness resolved into the clear, brilliant state of

the mind’s essential knowing nature, remaining absorbed in that subtle

knowing presence until normal awareness returned; and I then refocused with

increased vigor on the repetition of buddho.

It was during this stage that I first gained a solid spiritual

foundation in my meditation practice. From then on, my practice progressed

steadily—never again did it fall into decline. With each passing day, my

mind became increasingly calm, peaceful, and concentrated. The fluctuations,

that had long plagued me, ceased to be an issue. Concerns about the state of

my practice were replaced by mindfulness rooted in the present moment. The

intensity of this mindful presence was incompatible with thoughts of the

past or future. My center of activity was the present moment—each silent

repetition of buddho as it arose and passed away. I had no interest in

anything else. In the end, I was convinced that the reason for my mind’s

previous state of flux was the lack of mindfulness arising from not

anchoring my attention with a meditation-word. Instead, I had just focused

on a general feeling of inner awareness without a specific object, allowing

my mind to stray easily as thoughts intruded.

Once I understood the correct method for this initial stage of

meditation, I applied myself to the task with such earnest commitment that I

refused to allow mindfulness to lapse for even a single moment. Beginning in

the morning, when I awoke, and continuing until night, when I fell asleep, I

was consciously aware of my meditation at each and every moment of my waking

hours. It was a difficult ordeal, requiring the utmost concentration and

perseverance. I couldn’t afford to let down my guard and relax even for a

moment. Being so intently concentrated on the internalization of buddho, I

hardly noticed what went on around me. My normal daily interactions passed

by in a blur, but buddho was always sharply in focus. My commitment to the

meditation-word was total. With this firm foundation to bolster my practice,

mental calm and concentration became so unshakable that they felt as solid

and unyielding as a mountain.

Eventually this rock-solid condition of the mind became the primary

point of focus for mindfulness. As the citta steadily gained greater inner

stability, resulting in a higher degree of integration, the meditation-word

buddho gradually faded from awareness, leaving the calm and concentrated

state of the mind’s essential knowing nature to be perceived prominently on

its own. By that stage, the mind had advanced to samadhi—an intense state of

focused awareness, assuming a life of its own, independent of any meditation

technique. Fully calm and unified, the knowing presence itself became the

sole focus of attention, a condition of mind so prominent and powerful that

nothing else can arise to dislodge it. This is known as the mind being in a

state of continuous samadhi. In other words, the citta is samadhi—both are

one and the same.

Speaking in terms of the deeper levels of meditation practice, a

fundamental difference exists between a state of meditative calm and the

samadhi state. When the mind converges and drops into a calm, concentrated

state to remain for a period of time before withdrawing to normal

consciousness, this is known as meditative calm. The calm and concentration

are temporary conditions that last while the mind remains fixed in that

peaceful state. As normal consciousness returns, these extraordinary

conditions gradually dissipate. However, as the meditator becomes more adept

at this practice—entering into and withdrawing from a calm, unified state

over and over again—the mind begins to build a solid inner foundation. When

this foundation becomes unshakable in all circumstances, the mind is known

to be in a state of continuous samadhi. Then, even when the mind withdraws

from meditative calm it still feels solid and compact, as though nothing can

disturb its inward focus.

The citta that is continuously unified in samadhi is always even and

unperturbed. It feels completely satiated. Because of the very compact and

concentrated sense of inner unity, everyday thoughts and emotions no longer

make an impact. In such a state, the mind has no desire to think about

anything. Completely peaceful and contented within itself, nothing is felt

to be lacking.

In such a state of continuous calm and concentration, the citta

becomes very powerful. While the mind was previously hungry to experience

thoughts and emotions, it now shuns them as a nuisance. Before it was so

agitated that it couldn’t stop thinking and imagining even if it wanted to.

Now, with samadhi as its habitual condition, the mind feels no desire to

think about anything. It views thought as an unwanted disturbance. When the

mind’s essential knowing presence stands out prominently all the time, the

citta is so inwardly concentrated that it tolerates no disturbance. Because

of this sublime tranquility—and the tendency of samadhi to lull the mind

into this state of serene satisfaction—those whose minds have attained

continuous samadhi tend to become strongly attached to it. It remains so

until one reaches the level of practice where wisdom prevails, and the

results become even more satisfying.

FROM THEN ON I ACCELERATED MY EFFORTS. It was at that time that I began

sitting in meditation all night long, from dusk until dawn. While sitting

one night I started focusing inward as usual. Because it had already

developed a good, strong foundation, the citta easily entered into samadhi.

So long as the citta rested there calmly, it remained unaware of external

bodily feelings. But when I withdrew from samadhi many hours later I began

to experience them in full. Eventually, my body was so racked by severe pain

that I could hardly cope. The citta was suddenly unnerved, and its good,

strong foundation completely collapsed. The entire body was filled with such

excruciating pain that it quivered all over.

Thus began the bout of hand-to-hand combat that gave me insight into

an important meditation technique. Until the unexpected appearance that

night of such severe pain, I had not thought of trying to sit all night. I

had never made a resolution of that kind. I was simply practicing seated

meditation as I normally did, but when the pain began to overwhelm me, I

thought: “Hey, what’s going on here? I must make every effort to figure out

this pain tonight.” So I made the solemn resolve that no matter what

happened I would not get up from my seat until dawn of the next day. I was

determined to investigate the nature of pain until I understood it clearly

and distinctly. I would have to dig deep. But, if need be, I was willing to

die in order to find out the truth about pain.

Wisdom began to tackle this problem in earnest. Before I found myself

cornered like that with no way out, I never imagined that wisdom could be so

sharp and incisive. It went to work, relentlessly whirling around as it

probed into the source of the pain with the determination of a warrior who

never retreats or accepts defeat. This experience convinced me that in

moments of real crisis wisdom arises to meet the challenge. We are not fated

to be ignorant forever—when truly backed into a corner we are bound to be

able to find a way to help ourselves. It happened to me that night. When I

was cornered and overwhelmed by severe pain, mindfulness and wisdom just dug

into the painful feelings.

The pain began as hot flashes along the backs of my hands and feet,

but that was really quite mild. When it arose in full force, the entire body

was ablaze with pain. All the bones, and the joints connecting them, were

like fuel feeding the fire that engulfed the body. It felt as though every

bone in my body was breaking apart; as though my neck would snap and my head

drop to the floor. When all parts of the body hurt at once, the pain is so

intense that one doesn’t know how to begin stemming the tide long enough

just to breathe.

This crisis left mindfulness and wisdom with no alternative but to dig

down into the pain, searching for the exact spot where it felt most severe.

Mindfulness and wisdom probed and investigated right where the pain was

greatest, trying to isolate it so as to see it clearly. “Where does this

pain originate? Who suffers the pain?” They asked these questions of each

bodily part and found that each one of them remained in keeping with its own

intrinsic nature. The skin was skin, the flesh was flesh, the tendons were

tendons, and so forth. They had been so from the day of birth. Pain, on the

other hand, is something that comes and goes periodically; it’s not always

there in the same way that flesh and skin are. Ordinarily, the pain and the

body appear to be all bound up together. But are they really?

Focusing inward I could see that each part of the body was a physical

reality. What is real stays that way. As I searched the mass of bodily pain,

I saw that one point was more severe than all the others. If pain and body

are one, and all parts of the body are equally real, then why was the pain

stronger in one part than in another? So I tried to separate out and isolate

each aspect. At that point in the investigation, mindfulness and wisdom were

indispensable. They had to sweep through the areas that hurt and then whirl

around the most intense ones, always working to separate the feeling from

the body. Having observed the body, they quickly shifted their attention to

the pain, then to the citta. These three: body, pain and citta, are the

major principles in this investigation.

Although the bodily pain was obviously very strong, I could see that

the citta was calm and unafflicted. No matter how much discomfort the body

suffered, the citta was not distressed or agitated. This intrigued me.

Normally the kilesas join forces with pain, and this alliance causes the

citta to be disturbed by the body’s suffering. This prompted wisdom to probe

into the nature of the body, the nature of pain and the nature of the citta

until all three were perceived clearly as separate realities, each true in

its own natural sphere.

I saw clearly that it was the citta that defined feeling as being

painful and unpleasant. Otherwise, pain was merely a natural phenomenon that

occurred. It was not an integral part of the body, nor was it intrinsic to

the citta. As soon as this principle became absolutely clear, the pain

vanished in an instant. At that moment, the body was simply the body—a

separate reality on its own. Pain was simply feeling, and in a flash that

feeling vanished straight into the citta. As soon as the pain vanished into

the citta, the citta knew that the pain had disappeared. It just vanished

without a trace.

In addition, the entire physical body vanished from awareness. At that

moment I was not consciously aware of the body at all. Only a simple and

harmonious awareness remained, alone on its own. That’s all. The citta was

so exceedingly refined as to be indescribable. It simply knew—a profoundly

subtle inner state of awareness pervaded. The body had completely

disappeared. Although my physical form still sat in meditation, I was

completely unconscious of it. The pain too had disappeared. No physical

feelings were left at all. Only the citta’s essential knowing nature

remained. All thinking had stopped; the mind was not forming a single

thought. When thinking ceases, not the slightest movement disturbs the inner

stillness. Unwavering, the citta remains firmly fixed in its own solitude.

Due to the power of mindfulness and wisdom, the hot, searing pain that

afflicted my body had vanished completely. Even my body had disappeared from

consciousness. The knowing presence existed alone, as though suspended in

midair. It was totally empty, but at the same time vibrantly aware. Because

the physical elements did not interact with it, the citta had no sense that

the body existed. This knowing presence was a pure and solitary awareness

that was not connected to anything whatsoever. It was awesome, majestic and

truly magnificent.

It was an incredibly amazing experience. The pain was completely gone.

The body had disappeared. An awareness so fine and subtle that I cannot

describe it was the only thing not to disappear. It simply appeared, that’s

all I can say. It was a truly amazing inner state of being. There was no

movement—not even the slightest rippling—inside the citta. It remained fully

absorbed in stillness until enough time had elapsed, then it stirred as it

began to withdraw from samadhi. It rippled briefly and then went quiet

again.

This rippling happens naturally of its own accord. It cannot be

intended. Any intention brings the citta right back to normal consciousness.

When the citta absorbed in stillness has had enough, it begins to stir. It

is aware that a ripple stirs briefly and then ceases. Some moments later it

ripples briefly again, disappearing in the same instant. Gradually, the

rippling becomes more and more frequent. When the citta has converged to the

very base of samadhi, it does not withdraw all at once. This was very

evident to me. The citta rippled only slightly, meaning that a sankhara

formed briefly only to disappear before it could become intelligible. Having

rippled, it just vanished. Again and again it rippled and vanished,

gradually increasing in frequency until my citta eventually returned to

ordinary consciousness. I then became aware of my physical presence, but the

pain was still gone. Initially I felt no pain at all, and only slowly did it

begin to reappear.

This experience reinforced the solid spiritual foundation in my heart

with an unshakable certainty. I had realized a basic principle in contending

with pain: pain, body and citta are all distinctly separate phenomena. But

because of a single mental defilement—delusion—they all converge into one.

Delusion pervades the citta like an insidious poison, contaminating our

perceptions and distorting the truth. Pain is simply a natural phenomenon

that occurs on its own. But when we grab hold of it as a burning discomfort,

it immediately becomes hot—because our defining it in that way makes it hot.

After awhile the pain returned, so I had to tackle it again—without

retreating. I probed deep into the painful feelings, investigating them as I

had done before. But this time I could not use the same investigative

techniques that I had previously used to such good effect. Techniques

employed in the past were no longer relevant to the present moment. In order

to keep pace with internal events as they unfolded I needed fresh tactics,

newly devised by mindfulness and wisdom and tailor-made for present

circumstances. The nature of the pain was still the same, but the tactics

had to be suitable to the immediate conditions. Even though I had used them

successfully once before, I could not remedy the new situation by holding on

to old investigative techniques. Fresh, innovative techniques were required,

ones devised in the heat of battle to deal with present-moment conditions.

Mindfulness and wisdom went to work anew, and before long the citta once

again converged to the very base of samadhi.

During the course of that night the citta converged like this three

times, but I had to engage in bouts of hand-to-hand combat each time. After

the third time, dawn came, bringing to a close that decisive showdown. The

citta emerged bold, exultant and utterly fearless. Fear of death ceased that

night.

PAINFUL FEELINGS ARE JUST naturally occurring phenomena that constantly

fluctuate between mild and severe. As long as we do not make them into a

personal burden, they don’t have any special meaning for the citta. In and

of itself, pain means nothing, so the citta remains unaffected. The physical

body is also meaningless in and of itself, and it adds no meaning either to

feelings or to oneself—unless, of course, the citta invests it with a

specific meaning, gathering in the resultant suffering to burn itself.

External conditions are not really responsible for our suffering, only the

citta can create that.

Getting up that morning, I felt indescribably bold and daring. I

marveled at the amazing nature of my experience. Nothing comparable had ever

happened in my meditation before. The citta had completely severed its

connection with all objects of attention, converging inward with true

courage. It had converged into that majestic stillness because of my

thorough, painstaking investigations. When it withdrew, it was still full of

an audacious courage that knew no fear of death. I now knew the right

investigative techniques, so I was certain that I’d have no fear the next

time that pain appeared. It would, after all, be pain with just the same

characteristics. The physical body would be the same old body. And wisdom

would be the same faculty I’d used before. For this reason, I felt openly

defiant, without fear of pain or death.

Once wisdom had come to realize the true nature of what dies and what

does not, death became something quite ordinary. Hair, nails, teeth, skin,

flesh, bones: reduced to their original elemental form, they are simply the

earth element. Since when did the earth element ever die? When they

decompose and disintegrate, what do they become? All parts of the body

revert to their original properties. The earth and water elements revert to

their original properties, as do the wind and fire elements. Nothing is

annihilated. Those elements have simply come together to form a lump in

which the citta then takes up residence. The citta—the great master of

delusion—comes in and animates it, and then carries the entire burden by

making a self-identity out of it. “This is me, this belongs to me.”

Reserving the whole mass for itself, the citta accumulates endless amounts

of pain and suffering, burning itself with its own false assumptions.

The citta itself is the real culprit, not the lump of physical

elements. The body is not some hostile entity whose constant fluctuations

threaten our well-being. It is a separate reality that changes naturally

according to its own inherent conditions. Only when we make false

assumptions about it does it become a burden we must carry. That is

precisely why we suffer from bodily pain and discomfort. The physical body

does not produce suffering for us; we ourselves produce it. Thus I saw

clearly that no external conditions can cause us to suffer. We are the ones

who misconceive things, and that misconception creates the blaze of pain

that troubles our hearts.

I understood clearly that nothing dies. The citta certainly doesn’t

die; in fact, it becomes more pronounced. The more fully we investigate the

four elements, breaking them down into their original properties, the more

distinctly pronounced the citta appears. So where is death to be found? And

what is it that dies? The four elements—earth, water, wind and fire—they

don’t die. As for the citta, how can it die? It becomes more conspicuous,

more aware and more insightful. This essential knowing nature never dies, so

why is it so afraid of death? Because it deceives itself. For eons and eons

it has fooled itself into believing in death when actually nothing ever

dies.

So when pain arises in the body we must realize that it is merely

feeling, and nothing else. Don’t define it in personal terms and assume that

it is something happening to you. Pains have afflicted your body since the

day you were born. The pain that you experienced at the moment you emerged

from your mother’s womb was excruciating. Only by surviving such torment are

human beings born. Pain has been there from the very beginning and it’s not

about to reverse course or alter its character. Bodily pain always exhibits

the same basic characteristics: having arisen, it remains briefly and then

ceases. Arising, remaining briefly, ceasing—that’s all there is to it.

Investigate painful feelings arising in the body so as to see them

clearly for what they are. The body itself is merely a physical form, the

physical reality you have known since birth. But when you believe that you

are your body, and your body hurts, then you are in pain. Being equated,

body, pain and the awareness that perceives them then converge into one:

your painful body. Physical pain arises due to some bodily malfunction. It

arises dependent on some aspect of the body, but it is not itself a physical

phenomenon. Awareness of both body and feelings is dependent on the

citta—the one who knows them. But when the one who’s aware of them knows

them falsely, then concern about the physical cause of the pain and its

apparent intensity cause emotional pain to arise. Pain not only hurts but it

indicates that there is something wrong with you—your body. Unless you can

separate out these three distinct realities, physical pain will always cause

emotional distress.

The body is merely a physical phenomenon. We can believe whatever we

like about it, but that will not alter fundamental principles of truth.

Physical existence is one such fundamental truth. Four elemental

properties—earth, water, wind and fire—gather together in a certain

configuration to form what is called a “person”. This physical presence may

be identified as a man or a woman and be given a specific name and social

status, but essentially it is just the rupa khandha—a physical heap. Lumped

together, all the constituent parts form a human body, a distinct physical

reality. And each separate part is an integral part of that one fundamental

reality. The four elements join together in many different ways. In the

human body we speak of the skin, the flesh, the tendons, the bones, and so

forth. But don’t be fooled into thinking of them as separate realities

simply because they have different names. See them all as one essential

reality—the physical heap.

As for the heap of feelings, they exist in their own sphere. They are

not part of the physical body. The body isn’t feeling either. It has no

direct part in physical pain. These two khandhas—body and feeling—are more

prominent than the khandhas of memory, thought and consciousness, which,

because they vanish as soon as they arise, are far more difficult to see.

Feelings, on the other hand, remain briefly before they vanish. This causes

them to standout, making them easier to isolate during meditation.

Focus directly on painful feelings when they arise and strive to

understand their true nature. Confront the challenge head on. Don’t try to

avoid the pain by focusing your attention elsewhere. And resist any

temptation to wish for the pain to go away. The purpose of the investigation

must be a search for true understanding. The neutralization of pain is

merely a by-product of the clear understanding of the principles of truth.

It cannot be taken as the primary objective. That will only create the

conditions for greater emotional stress when the relief one wishes for fails

to materialize. Stoic endurance in the face of intense pain will not succeed

either. Nor will concentrating single-mindedly on pain to the exclusion of

the body and the citta. In order to achieve the proper results, all three

factors must be included in the investigation. The investigation must always

be direct and purposeful.

THE LORD BUDDHA TAUGHT US to investigate with the aim of seeing all pain as

simply a phenomenon that arises, remains briefly and then vanishes. Don’t

become entangled in it. Don’t view the pain in personal terms, as an

inseparable part of who you are, for that runs counter to pain’s true

nature. It also undermines the techniques used to investigate pain,

preventing wisdom from knowing the reality of feelings. Don’t create a

problem for yourself where none exists. See the truth as it arises in each

moment of pain, observing as it remains briefly and vanishes. That’s all

there is to pain.

When you have used mindfulness and wisdom to isolate the painful

feeling, turn your attention to the citta and compare the feeling with the

awareness that knows it to see if they really are inseparable. Turn and

compare the citta and the physical body in the same manner: are they in any

way identical? Focus clearly on each one and don’t allow your concentration

to wander from the specific point you are investigating. Keep it firmly

fixed on the one aspect. For instance, focus your full attention on the pain

and analyze it until you understand its distinguishing characteristics; then

turn to look at the citta and strive to see its knowing nature distinctly.

Are the two identical? Compare them. Are the feeling and the awareness that

knows it one and the same thing? Is there any way to make them so? And the

body, does it share similar characteristics with the citta? Is it like the

feeling? Are any of these three similar enough to be lumped together?

The body is physical matter—how can it be likened to the citta? The

citta is a mental phenomenon, an awareness that knows. The physical elements

that make up the body have no intrinsic awareness, they have no capacity to

know. The earth, water, wind and fire elements know nothing; only the mental

element—the manodhatu—knows. This being the case, how can the citta’s

essential knowing nature and the body’s physical elements possibly be

equated. They are obviously separate realities.

The same principle applies to pain. It has no intrinsic awareness, no

capacity to know. Pain is a natural phenomenon that arises in conjunction

with the body, but it is unaware of the existence of the body or of itself.

Painful feelings depend on the body as their physical basis. Without the

body they could not occur. But they have no physical reality of their own.

Sensations that arise in conjunction with the body are interpreted in such a

way that they become indistinguishable from the area of the body that is

affected. Instinctively, body and pain are equated, so the body itself seems

to hurt. We must remedy this instinctive reaction by investigating both the

characteristics of pain as a sense phenomenon and the purely physical

characteristics of that part of the body where that pain is felt acutely.

The objective is to determine clearly whether or not the physical

location—say a knee joint—exhibits the distinctive characteristics

associated with pain. What kind of shape and posture do they have? Feelings

have no shape or posture. They occur simply as an amorphous sensation. The

body does have a definite shape, color and complexion, and these are not

changed by the occurrence of physical feelings. It remains just the same as

it was before pain arose. The physical substance is in no way altered by

pain because pain, being a separate reality, has no direct effect on it.

For instance, when a knee hurts or a muscle hurts: knee and muscle are

merely bone, ligament and flesh. They themselves are not pain. Although the

two dwell together, they retain their own separate characteristics. The

citta knows both of these things but, because its awareness is clouded by

delusion, it automatically assumes that the pain is mixed in with the bones,

ligaments and muscles that compose a knee joint. By reason of that same

fundamental ignorance, the citta assumes that the body in all of its aspects

is an integral part of one’s very being. So the pain too becomes bound up

with one’s sense of being. “My knee hurts. I am in pain. But I don’t want to

suffer pain. I want the pain to go away.” This desire to get rid of pain is

a kilesa that increases the level of discomfort by turning physical feeling

into emotional suffering. The stronger the pain is, the stronger the desire

to rid oneself of it becomes, which leads to greater emotional distress.

These factors keep feeding each other. Thus, due to our own ignorance, we

load ourselves down with dukkha.

In order to see pain, body and citta as separate realities we must

view each from the proper perspective, a perspective that allows them to

float freely instead of coalescing into one. While they are bound together

as part of our self-image there is no independent viewpoint, and therefore

no effective means to separate them apart. As long as we insist on regarding

pain in personal terms, it will be impossible to breach this impasse. When

the khandhas and the citta are merged into one, we have no room to maneuver.

But when we investigate them with mindfulness and wisdom, moving back and

forth between them, analyzing each and comparing their specific features, we

notice definite distinctions among them and so see their true natures

clearly. Each exists on its own as a separate reality. This is a universal

principle.

As the profound nature of this realization sinks deep into the heart,

the pain begins to abate and gradually fades away. At the same time we

realize the fundamental connection between the experience of pain and the

“self” that grasps it. That connection is established from inside the citta

and extends outwardly to include the pain and the body. The actual

experience of pain emanates from the citta and its deep-seated attachment to

self, which causes emotional pain to arise in response to physical pain.

Fully aware the whole time, we follow the feeling of pain inward to its

source. As we focus on it, the pain we are investigating begins to retract,

gradually drawing back into the heart. Once we realize unequivocally that it

is actually the attachment created by the heart that causes us to experience

pain as a personal problem, the pain disappears. It may disappear

completely, leaving only the essential knowing nature of the citta alone on

its own. Or, the external phenomenon of pain may remain present but, because

the emotional attachment has been neutralized, it is no longer experienced

as painful. It is a different order of reality from the citta, and the two

do not interact. Since at that moment the citta has ceased to grasp at pain,

all connection has been severed. What’s left is the essence of the citta—its

knowing nature—serene and unperturbed amidst the pain of the khandhas.

No matter how severe the pain may be at that time, it will be unable

to affect the citta in any way. Once wisdom realizes clearly that the citta

and the pain are each real, but real in their own separate ways, the two

will not impact one another at all. The body is merely a lump of physical

matter. The same body that was there when the pain appeared is still there

when the pain ceases. Pain does not alter the nature of the body; the body

does not affect the nature of pain. The citta is the nature that knows that

the pain appears, remains briefly, and ceases. But the citta, the true

knowing essence, does not arise and pass away like the body and the feelings

do. The citta’s knowing presence is the one stable constant.

This being the case, pain—no matter how great—has no impact on the citta.

You can even smile while severe pain is arising—you can smile!—because the

citta is separate. It constantly knows but it does not become involved with

feelings so it does not suffer.

This level is attained through an intensive application of mindfulness

and wisdom. It’s a stage where wisdom develops samadhi. And because the

citta has fully investigated all aspects until they are understood

thoroughly, the citta reaches the full extent of samadhi at that time. It

converges with a boldness and subtlety so profound as to defy description.

This amazing awareness comes from analyzing things completely and

exhaustively and then withdrawing from them. Ordinarily, when the citta

relies on the power of samadhi meditation to converge into a calm,

concentrated state, it becomes still and quiet. But that samadhi state is

not nearly so subtle and profound as the one attained through the power of

wisdom. Once mindfulness and wisdom have engaged the kilesas in hand-to-hand

combat and triumphed, the nature of the calm that’s attained will be

spectacular each time.

This is the path for those who are practicing meditation so as to

penetrate to the truth of the five khandhas, using painful feeling as the

primary focus. This practice formed the initial basis for my fearlessness in

meditation. I saw with unequivocal clarity that the essential knowing nature

of the citta could never possibly be annihilated. Even if everything else

were completely destroyed, the citta would remain wholly unaffected. I

realized this truth with absolute clarity the moment when the citta’s

knowing essence stood alone on its own, completely uninvolved with anything

whatsoever. There was only that knowing presence standing out prominently,

awesome in its splendor. The citta lets go of the body, feeling, memory,

thought and consciousness and enters a pure stillness of its very own, with

absolutely no connection to the khandhas. In that moment, the five khandhas

do not function in any way at all in relation to the citta. In other words,

the citta and the khandhas exist independently because they have been

completely cut off from one another due to the persistent efforts of

meditation.

That attainment brings a sense of wonder and amazement that no

experience we’ve ever had could possibly equal. The citta stays suspended in

a serene stillness for a long time before withdrawing to normal

consciousness. Having withdrawn, it reconnects with the khandhas as before,

but it remains absolutely convinced that the citta has just attained a state

of extraordinary calm totally cut off from the five khandhas. It knows that

it has experienced an extremely amazing spiritual state of being. That

certainty will never be erased.

Due to that unshakable conviction, which became fixed in my heart as a

result of that experience and therefore could not be brought into doubt by

unfounded or unreasonable assertions, I resumed my earlier samadhi

meditation in earnest—this time with an added determination and a sense of

absorption stemming from the magnetic pull that this certainty has in the

heart. The citta was quick to converge into the calm and concentration of

samadhi as before. Although I could not yet release the citta completely

from the infiltration of the five khandhas, I was greatly inspired to make a

persistent effort to reach the higher levels of Dhamma.

NO MATTER HOW DEEP OR CONTINUOUS, samadhi is not an end in itself. Samadhi

does not bring about an end to all suffering. But samadhi does constitute an

ideal platform from which to launch an all out assault on the kilesas that

cause all suffering. The profound calm and concentration generated by

samadhi form an excellent basis for the development of wisdom.

The problem is that samadhi is so peaceful and satisfying that the

meditator inadvertently becomes addicted to it. This happened to me: for

five years I was addicted to the tranquility of samadhi; so much so that I

came to believe that this very tranquility was the essence of Nibbana. Only

when my teacher, Acariya Mun, forced me to confront this misconception, was

I able to move on to the practice of wisdom.

Unless it supports the development of wisdom, samadhi can sidetrack a

meditator from the path to the end of all suffering. All meditators who

intensify their efforts to develop samadhi should be aware of this pitfall.

Samadhi’s main function on the path of practice is to support and sustain

the development of wisdom. It is well suited to this task because a mind

that is calm and concentrated is fully satisfied, and does not seek external

distractions. Thoughts about sights, sounds, tastes, smells, and tactile

sensations no longer impinge upon an awareness that is firmly fixed in

samadhi. Calm and concentration are the mind’s natural sustenance. Once it

becomes satiated with its favorite nourishment, it does not wander off where

it strays into idle thinking. It is now fully prepared to undertake the kind

of purposeful thinking, investigation and reflection that constitute the

practice of wisdom. If the mind has yet to settle down—if it still hankers

after sense impressions, if it still wants to chase after thoughts and

emotions—its investigations will never lead to true wisdom. They will lead

only to discursive thought, guesswork and speculation—unfounded

interpretations of reality based simply on what has been learned and

remembered. Instead of leading to wisdom, and the cessation of suffering,

such directionless thinking becomes samudaya—the primary cause of suffering.

Since its sharp, inward focus complements the investigative and

contemplative work of wisdom so well, the Lord Buddha taught us to first

develop samadhi. A mind that remains undistracted by peripheral thoughts and

emotions is able to focus exclusively on whatever arises in its field of

awareness and to investigate such phenomena in light of the truth without

the interference of guesswork or speculation. This is an important

principle. The investigation proceeds smoothly, with fluency and skill. This

is the nature of genuine wisdom: investigating, contemplating and

understanding, but never being distracted or misled by conjecture.

The practice of wisdom begins with the human body, the grossest and

most visible component of our personal identity. The object is to penetrate

the reality of its true nature. Is our body what we’ve always assumed it to

be—an integral and desirable part of who we really are? To test this

assumption we must thoroughly investigate the body by mentally

deconstructing it into its constituent parts, section by section, piece by

piece. We must research the truth about the body with which we are so

familiar by viewing it from different angles. Begin with the hair on the

head, the hair on the body, the nails, the teeth and the skin, and move on

to the flesh, blood, sinews and bones. Then dissect the inner organs, one by

one, until the whole body is completely dismembered. Analyze this

conglomeration of disparate parts to clearly understand its true nature.

If you find it difficult to investigate your own body in this way,

begin by mentally dissecting someone else’s body. Choose a body external to

yourself; for instance, a body of the opposite sex. Visualize each part,

each organ of that body as best you can, and ask yourself: Which piece is

truly attractive? Which part is actually seductive? Place the hair in one

pile, the nails and teeth in another; do the same with the skin, the flesh,

the sinews and the bones. Which pile deserves to be an object of your

desire? Examine them closely and answer with total honesty. Strip off the

skin and pile it in front of you. Where is the beauty in this mass of

tissue, this thin veneer that covers up the meat and entrails? Do those

various parts add up to a person? Once the skin is removed, what can we find

to admire in the human body? Men and women—they are all the same. Not a

shred of beauty can be found in the body of a human being. It is just a bag

of flesh and blood and bones that manages to deceive everyone in the world

into lusting after it.

It is wisdom’s duty to expose that deception. Examine the skin

carefully. Skin is the great deceiver. Because it wraps up the entire human

body, it’s the part we always see. But what does it wrap up? It wraps up the

animal flesh, the muscles, the fluids and the fat. It wraps up the skeleton

with the tendons and the sinews. It wraps up the liver, the kidneys, the

stomach, the intestines, and all the internal organs. No one has ever

suggested that the body’s innards are desirable things of beauty, worthy of

being admired with passion and yearning. Probing deeply, without fear or

hesitation, wisdom exposes the plain truth about the body. Don’t be fooled

by a thin veil of scaly tissue. Peel it off and see what lies underneath.

This is the practice of wisdom.

In order to really see the truth of this matter for yourself, in a

clear and precise way that leaves no room for doubt, you must be very

persistent and very diligent. Merely doing this meditation practice once or

twice, or from time to time, will not be enough to bring conclusive results.

You must approach the practice as if it’s your life’s work—as though nothing

else in the world matters except the analysis you are working on at that

moment. Time is not a factor; place is not a factor; ease and comfort are

not factors. Regardless of how long it takes or how difficult the work

proves to be, you must relentlessly stick with body contemplation until all

doubt and uncertainty are eliminated.

Body contemplation should occupy every breath, every thought, every

movement until the mind becomes thoroughly saturated with it. Nothing short

of total commitment will bring genuine and direct insight into the truth.

When body contemplation is practiced with single-minded intensity, each

successive body part becomes a kind of fuel feeding the fires of mindfulness

and wisdom. Mindfulness and wisdom then become a conflagration consuming the

human body section by section, part by part, as they examine and investigate

the truth with a burning intensity. This is what is meant by tapadhamma.

Focus intently on those body parts that really capture your attention,

the ones whose truth feels most obvious to you. Use them as whetstones to

sharpen your wisdom. Expose them and tear them apart until their inherently

disgusting and repulsive nature becomes apparent. Asubha meditation is

insight into the repulsiveness of the human body. This is the body’s natural

condition; by nature, it is filthy and disgusting. Essentially, the whole

body is a living, stinking corpse—a breathing cesspool full of fetid waste.

Only a paper thin covering of skin makes the whole mess look presentable. We

are all being deceived by the outer wrapping, which conceals the fundamental

repulsiveness from view. Merely removing the skin reveals the body’s true

nature.

By comparison to the flesh and internal organs, the skin appears

attractive. But examine it more closely. Skin is scaly, creased, and

wrinkled; it exudes sweat and grease and offensive odors. We must scrub it

daily just to keep it clean. How attractive is that? And the skin is firmly

wedded to the underlying flesh, and thus inextricably linked to the

loathsome interior. The more deeply wisdom probes, the more repulsive the

body appears. From the skin on through to the bones, nothing is the least

bit pleasing.

PROPERLY DONE, BODY CONTEMPLATION is intense and the mental effort is

unrelenting; so, eventually, the mind begins to tire. It is then appropriate

to stop and take a rest. When meditators who are engaged in full-scale body

contemplation take a break, they return to the samadhi practice they have

developed and maintained so assiduously. Reentering the still peace and

concentration of samadhi, they abide in total calm where no thoughts or

visualizations arise to disturb the citta. The burden of thinking and

probing with wisdom is temporarily set aside so that the mind can completely

relax, suspended in tranquility. Once the mind is satiated with samadhi, it

withdraws on its own, feeling reinvigorated and refreshed and ready to

tackle the rigors of body contemplation again. In this way, samadhi supports

the work of wisdom, making it more adept and incisive.

Upon withdrawal from samadhi, the investigation of the body

immediately begins anew. Each time you investigate with mindfulness and

wisdom, the investigation should be carried out in the present moment. To be

fully effective, each new investigation must be fresh and spontaneous. Don’t

allow them to become carbon copies of previous ones. An immediacy, of being

exclusively in the present moment, must be maintained at all times. Forget

whatever you may have learned; forget what happened the last time you delved

into the body’s domain—just focus your attention squarely in the present

moment and investigate only from that vantage point. Ultimately, this is

what it means to be mindful. Mindfulness fixes the mind in the present,

allowing wisdom to focus sharply. Learned experience is stored as memory,

and as such should be put aside; otherwise memory will masquerade as wisdom.

This is the present imitating the past. If memory is permitted to replace

the immediacy of the present moment, then genuine wisdom will not arise. So

guard against this tendency in your practice.

Keep probing and analyzing the nature of the body over and over again,

using as many perspectives as your wisdom can devise, until you become

thoroughly skilled in every conceivable aspect of body contemplation. True

expertise in this practice produces sharp, clear insights. It penetrates

directly to the essence of the body’s natural existence in a way that

transforms the meditator’s view of the human body. A level of mastery can be

reached, such that peoples’ bodies instantly appear to break apart whenever

you look at them. When wisdom attains total mastery of the practice, we see

only flesh, sinews and bones where a person once stood. The whole body is

revealed as a viscous, red mass of raw tissue. The skin will vanish in a

flash, and wisdom will quickly penetrate the body’s inner recesses. Whether

it’s a man or a woman, the skin—which is commonly considered so appealing—is

simply ignored. Wisdom penetrates immediately inside where a disgusting,

repulsive mess of organs and bodily fluids fills every cavity.

Wisdom is able to penetrate to the truth of the body with utmost

clarity. The attractiveness of the body completely disappears. What then is

there to be attached to? What is there to lust after? What in the body is

worth clinging to? Where in this lump of raw flesh is the person? The

kilesas have woven a web of deception concerning the body, fooling us with

perceptions of human beauty and exciting us with lustful thoughts. The truth

is that the object of that desire is a fake—a complete fraud. For in

reality, when seen clearly with wisdom, the body by its very nature repels

desire. When this delusion is exposed in the light of wisdom, the human body

appears in all its gory detail as an appalling sight. Seen with absolute

clarity, the mind shrinks from it instantly.

The keys to success are persistence and perseverance. Always be

diligent and alert when applying mindfulness and wisdom to the task. Don’t

be satisfied with partial success. Each time you contemplate the body, carry

that investigation through to its logical conclusion; then quickly

reestablish an image of the body in your mind and begin the process all over

again. As you delve deeper and deeper into the body’s interior, the various

parts will gradually begin to break up, fall apart, and disintegrate right

before your eyes. Follow the process of disintegration and decay intently.

Mindful of every detail, focus your wisdom on the unstable and impermanent

nature of this form that the world views with such infatuation. Let your

intuitive wisdom initiate the process of decay and see what happens. This is

the next stage in body contemplation.

Follow the natural conditions of decay as the body decomposes and

returns to its original elemental state. Decay and destruction is the

natural course of all organic life. Eventually, all things are reduced to

their constituent elements, and those elements disperse. Let wisdom be the

destroyer, imagining for the mind’s eye the process of decay and

decomposition. Concentrate on the disintegration of the flesh and other soft

tissue, watching as it slowly decomposes until nothing remains but

disjointed bones. Then reconstruct the body again and begin the

investigation once more. Each time that intuitive wisdom lays waste to the

body, mentally restore it to its former condition and start anew.

This practice is an intense form of mental training, requiring a high

degree of skill and mental fortitude. The rewards reflect the power and

intensity of the effort made. The more proficient wisdom is, the brighter,

clearer and more powerful the mind becomes. The mind’s clarity and strength

appear to have no bounds—its speed and agility are amazing. At this stage,

meditators are motivated by a profound sense of urgency as they begin to

realize the harm caused by attachment to the human form. The lurking danger

is clearly seen. Where previously they grasped the body as something of

supreme value—something to be admired and adored—they now see only a pile of

rotting bone; and they are thoroughly repulsed. Through the power of wisdom,

a dead, decaying body and the living, breathing body have become one and the

same corpse. Not a shred of difference exists between them.

You must investigate repeatedly, training the mind until you become

highly proficient at using wisdom. Avoid any form of speculation or

conjecture. Don’t allow thoughts of what you should be doing or what the

results might mean to encroach upon the investigation. Just concentrate on

the truth of what wisdom reveals and let the truth speak for itself. Wisdom

will know the correct path to follow and will understand clearly the truths

that it uncovers. And when wisdom is fully convinced of the truth of any

aspect of the body, it will naturally release its attachment to that aspect.

No matter how intently it has pursued that investigation, the mind feels

fully satisfied once the truth manifests itself with absolute certainty.

When the truth of one facet of body contemplation is realized, there is

nothing further to seek in that direction. So, the mind moves on to examine

another facet, and then another facet, until finally all doubts are

eliminated.

Striving in this way, probing deeper and deeper into the body’s

inherent nature with an intense focus on the present moment, a heightened

state of awareness must be maintained; and the intensity of the effort

eventually takes its toll. When fatigue sets in, experienced meditators know

instinctively that the time is right to rest the mind in samadhi. So they

drop all aspects of the investigation and concentrate solely on one object.

Totally unburdening themselves, they enter into the cool, composed,

rejuvenating peace of samadhi. In this way, samadhi is a separate practice

altogether. No thoughts of any kind infringe upon the citta’s essential

knowing nature while it rests peacefully with single-minded concentration.

With the citta absorbed in total stillness, the body and the external world

temporarily disappear from awareness. Once the citta is satiated, it

withdraws to normal consciousness on its own. Like a person who eats a full

meal and takes a good rest, mindfulness and wisdom are refreshed and ready

to return to work with renewed energy. Then, with purposeful resolve, the

practice of samadhi is put aside and the practice of wisdom is

reestablished. In this way, samadhi is an outstanding complement to wisdom.

THE BODY IS VERY IMPORTANT TO CONSIDER. Most of our desires are bound up

with it. Looking around us, we can see a world that is in the grips of

sexual craving and frantic in its adoration of the human form. As

meditators, we must face up to the challenges posed by our own sexuality,

which stems from a deep-seated craving for sensual gratification. During

meditation, this defilement is the most significant obstacle to our

progress. The deeper we dig into body contemplation, the more evident this

becomes. No other form of kilesa drags more on the mind, nor exerts greater

power over the mind than the defilement of sexual craving. Since this

craving is rooted in the human body, exposing its true nature will gradually

loosen the mind’s tenacious grasp on the body.

Body contemplation is the best antidote for sexual attraction.

Successful body practice is measured by a reduction in the mind’s sexual

desires. Step by step, wisdom unmasks the reality of the body, cutting off

and destroying deep-rooted attachments in the process. This results in an

increasingly free and open mental state. To fully understand their

significance, meditators must experience these results for themselves. It

would be counter-productive for me to try to describe them—that would only

lead to fruitless speculation. These results arise exclusively within a

meditator’s mind, and are unique to that person’s character and temperament.

Simply focus all your attention on the practical causes and let the results

of that effort arise as they will. When they do, you will know them with

undeniable clarity. This is a natural principle.

When body contemplation reaches the stage where reason and result

become fully integrated with wisdom, one becomes completely absorbed in

these investigations both day and night. It’s truly extraordinary. Wisdom

moves through the body with such speed and agility, and displays such

ingenuity in its contemplative techniques, that it seems to spin

relentlessly in and out and around every part, every aspect of the body,

delving into each nook and cranny to discover the truth. At this stage of

the practice, wisdom begins to surface automatically, becoming truly

habitual in manifesting itself. Because it’s so quick and incisive, it can

catch up with even the most subtle kilesas, and disable even the most

indomitable ones. Wisdom at this level is extremely daring and adventurous.

It is like a mountain torrent crashing through a narrow canyon: nothing can

deter its course. Wisdom bursts forth to meet every challenge to crave and

to cling that is presented by the kilesas. Because its adversary is so

tenacious, wisdom’s battle with sexual craving resembles a full-scale war.

For this reason, only a bold and uncompromising strategy will succeed. There

is only one appropriate course of action—an all out struggle; and the

meditator will know this instinctively.

When wisdom begins to master the body, it will constantly modify its

investigative techniques so that it will not fall prey to the tricks of the

kilesas. Wisdom will try to keep one step ahead of the kilesas, constantly

looking for new openings and constantly adjusting its tactics: sometimes

shifting emphasis, sometimes pursuing subtle variations in technique.

As greater and greater proficiency is achieved, there comes a time

when all attachment to one’s own body and to that of others appears to have

vanished. In truth, a lingering attachment still remains; it has only gone

into hiding. It has not been totally eliminated. Take careful note of this.

It may feel as though it is eliminated, but actually it is concealed from

view by the power of the asubha practice. So don’t be complacent. Keep

upgrading your arsenal—mindfulness, wisdom and diligence—to meet the

challenge. Mentally place the whole mass of body parts in front of you and

focus on it intently. This is your body. What will happen to it? By now

wisdom is so swift and decisive that in no time at all it will break up and

disintegrate before your eyes. Each time you spread the body out before

you—whether it is your body or someone else’s—wisdom will immediately begin

to break it apart and destroy it. By now this action has become habitual.

In the end, when wisdom has achieved maximum proficiency at

penetrating to the core of the body’s repulsive nature, you must place the

entire disgusting mess of flesh and blood and bones in front of you and ask

yourself: From where does this feeling of revulsion emanate? What is the

real source of this repulsiveness? Concentrate on the disgusting sight

before you and see what happens. You are now closing in on the truth of the

matter. At this crucial stage in asubha contemplation, you must not allow

wisdom to break the body apart and destroy it.

Fix the repulsive image clearly in your mind and watch closely to

detect any movement in the repulsive feeling. You have evoked a feeling of

revulsion for it: Where does that feeling originate? From where does it

come? Who or what assumes that flesh, blood and bones are disgusting? They

are as they are, existing in their own natural state. Who is it that

conjures up feelings of revulsion at their sight? Fix your attention on it.

Where will the repulsiveness go? Wherever it moves, be prepared to follow

its direction.

The decisive phase of body contemplation has been reached. This is the

point where the root-cause of sexual craving is uprooted once and for all.

As you focus exclusively on the repulsiveness evoked by the asubha

contemplation, your revulsion of the image before you will slowly, gradually

contract inward until it is fully absorbed by the mind. On its own, without

any prompting, it will recede into the mind, returning to its source of

origin. This is the decisive moment in the practice of body contemplation,

the moment when a final verdict is reached about the relationship between

the kilesa of sexual craving and its primary object, the physical body. When

the mind’s knowing presence fully absorbs the repulsiveness, internalizing

the feeling of revulsion, a profound realization suddenly occurs: The mind

itself produces feelings of revulsion, the mind itself produces feelings of

attraction; the mind alone creates ugliness and the mind alone creates

beauty.

These qualities do not really exist in the external physical world. The mind

merely projects these attributes onto the objects it perceives and then

deceives itself into believing that they are beautiful or ugly, attractive

or repulsive. In truth, the mind paints elaborate pictures all the

time—pictures of oneself and pictures of the external world. It then falls

for its own mental imagery, believing it to be real.

At this point the meditator understands the truth with absolute

certainty: The mind itself generates repulsion and attraction. The previous

focus of the investigation—the pile of flesh and blood and bones—has no

inherent repulsiveness whatsoever. Intrinsically, the human body is neither

disgusting nor pleasing. Instead, it is the mind that conjures up these

feelings and then projects them on the images that are in front of us. Once

wisdom penetrates this deception with absolute clarity, the mind immediately

relinquishes all external perceptions of beauty and ugliness, and turns

inward to concentrate on the source of such notions. The mind itself is the

perpetrator and the victim of these deceptions; the deceiver and the

deceived.

Only the mind, and nothing else, paints pictures of beauty and ugliness. So

the asubha images that the meditator has been focusing on as separate and

external objects, are absorbed into the mind where they merge with the

revulsion created by the mind. Both are, in fact, one and the same thing.

When this realization occurs, the mind lets go of external images, lets go

of external forms, and in doing so lets go of sexual attraction.

Sexual attraction is rooted in perceptions of the human body. When the

real basis of these perceptions is exposed, it completely undermines their