Several years ago, while I was

preparing for a trip to South-east Asia–in part to learn about

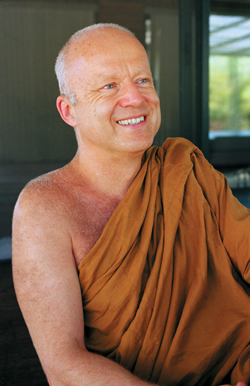

Buddhism–a friend suggested that I first contact Thanissaro Bhikkhu,

the abbot of the Metta Forest Monastery in northern San Diego County.

Despite his imposing Thai name, this monk was actually raised in rural

New York and Virginia under an equally imposing American name:

Geoffrey Furguson DeGraff.

As an Oberlin student, Geoff was

introduced to meditation during a winter-term seminar in 1969. He

graduated in 1971, and then served as a Shansi rep in Thailand for two

years. After returning there in 1976, he was ordained a monk and spent

the next 15 years immersed in the Forest monastery tradition of

Theravada Buddhism (see sidebar). He returned to the United States in

1991 to establish the Metta Forest Monastery, an American equivalent

of the Thai Forest retreats.

Known informally as "Than Geoff,"

Thanissaro Bhikkhu has written several books on Buddhism and Vipassana

(Insight) meditation. Fluent in Thai and Pali, the languages of early

Buddhist writings, he has translated the writings of two noted Thai

abbots and four volumes of the Pali Canon. In short, he knows his

Buddhism.

Although I was anxious during our

first phone call, Than Geoff was relaxed and friendly. He started me

on an exploration into Buddhism that I've both embraced and tried to

avoid almost every day since. Over the years, we've had lengthy

conversations about almost everything. But I still had countless

questions for him–personal questions I suspected other people also

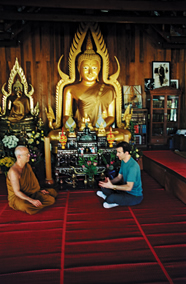

would like to ask a monk. When I suggested an interview, Than Geoff

replied instantly, "Sounds like fun." A few months later, on a warm

September afternoon at his monastery, Than Geoff and I began to talk.

You arrived at Oberlin as a freshman in

1967. I assume you chose Oberlin because you knew it would give you

the best undergraduate training possible to become a Buddhist monk.

That was the last thing on my mind. As a junior in high school reading

American history, I read how Oberlin was among the first coed and

integrated colleges in the country, and that interested me. I also

liked that it had classical music. I was a classical music fanatic.

The Thai Forest Tradition,

founded in the late 19th century, is known for its strict

adherence to monastic discipline and its emphasis on the

full-time practice of meditation. The tradition derives from the

belief that the Buddha himself gained awakening in a forest,

gave his first sermon in a forest, and passed away in a forest.

The qualities of mind he developed to survive in the wild–both

physically and mentally–were key to his teachings.

|

Did Oberlin give

you your first exposure to Buddhism?

No. In high school, I had been an American Friends Service (AFS)

student in the Philippines. On the plane coming back home, I met two

guys who had been to Thailand and been ordained as novices (a kind of

apprentice monk). They explained the Four Noble Truths, the most

fundamental teaching of the Buddha. It made a lot of sense to me.

Also, my girlfriend's father was a military man who had been stationed

in Thailand. She had lots of stories to tell about Thailand as well. I

was intrigued.

Did your interest grow at Oberlin?

During my sophomore year, during Oberlin's very first winter term, Don

Swearer, a professor of religion, brought in a monk from Japan and a

monk from Thailand to teach meditation. I signed up immediately. I

remember thinking, "This is a really cool skill. You sit down and

breathe, and you come up an hour later a much better person." That's

what I liked about meditation from the beginning: learning how to

bring your mind under control and find happiness inside.

Did you consider yourself an

unhappy person?

I think everybody in college considers themselves unhappy.

Did

a light bulb go off in your head during that winter term? Did you

suddenly decide, "I'm becoming a monk!"

Did

a light bulb go off in your head during that winter term? Did you

suddenly decide, "I'm becoming a monk!"

I wanted to go to Thailand with the Peace Corps. Instead, I went with

the Shansi program with the idea that I'd find a meditation teacher

and learn a few basic skills. At the end of my Shansi term, I met

Ajaan Fuang, a member of the Forest tradition, who became my teacher.

I was going to extend my time in Thailand, but I caught malaria. So I

disrobed and came back.

I planned to get my graduate degree in religion and teach Buddhism. I

went to an American Academy of Religion conference in Chicago, where

the three big names in Thai Buddhism gave presentations. About 10

people showed up. And there was no dialogue going on at all. I

thought, "I can't do this with my life." I kept thinking about Ajaan

Fuang on his hillside with not much to his name–yet perfectly happy.

So you returned to Thailand. Did you intend

to become a monk?

You really have to be a monk to have a full-time opportunity to

meditate. You have whole days to yourself to work on your greed,

anger, and delusions. It seemed like an ideal situation.

I stayed with Ajaan Fuang for another 10 years. I became his

attendant, the monk who looked after him when he was sick. Before he

died in 1986, he made it known that he wanted me to take over the

monastery in Thailand. There was no precedent for a Westerner taking

over a temple that had been founded by and for Thai monks, so it was

pretty controversial.

By the time I was offered the position of abbot there, so many strings

were attached that it would have been all responsibility and no

authority. It was then that Ajaan Suwat sought me out and asked me to

help him here in California.

Ajaan Suwat is a Thai monk who founded a Buddhist Forest monastery

in a suburb of Orange County, California.

They tried to maintain the traditions of a Forest monastery. They

planted a lot of trees to make it a nice, foresty kind of place. But

the city environment had taken over. Ajaan Suwat had begun looking for

a new place in a forest and had identified this spot near San Diego. A

young man who had just come into an inheritance offered to buy it.

Ajaan Suwat asked me, "Are you going to come help me with this? If

not, I can't accept the money. Because I can't run two monasteries at

once."

I didn't have to think twice. I said, "Yes."

What's a typical day like for you? It's 8

a.m. and the alarm goes off…

I get up at 4.

You set your alarm for 4 a.m?!

I pretty much just wake up now. If I had a long night the night

before, maybe 5. Then I get up and meditate for about two hours.

By yourself or with a group?

By myself.

Are there ever days when it's difficult to

drag yourself out of bed?

There are times when I say, "I think I'll do some lying-down

meditation."

I'd be great at that.

It's legit. For me, the early morning is the best time to meditate.

There's always the thought that if I don't get up and meditate now,

I'll miss this chance. It's still cool outside. There's an extra-quiet

atmosphere.

I meditate until dawn, and then I come here [to the common area by the

temple] and help sweep and clean up with the other monks.

Does a gong go off, or do you just know

when it's time to stop meditating?

I know. And I have my little beeper watch.

In Thailand, monks go for alms rounds every

morning to get food, leaving the monastery and carrying a bowl into

which people put food. What happens in San Diego? Do you hop in an SUV

and drive through the local suburbs?

We go with our bowls to the guesthouse. People prepare food in the

kitchen.

Who's there?

People who are visiting the monastery and meditating, candidates for

the monkhood. A young guy who works in the orchard is sometimes there.

We also have Thai and Laotian people who come up just to present food.

You get one meal a day. Are you getting

enough fiber? Are you getting enough protein?

I weigh 30 pounds more than when I graduated from Oberlin.

But don't you get hungry?

That first year in Thailand was hard, as my body was adjusting to the

change in diet and metabolism. I was in a very ascetic mood, so I

didn't mind that I got really thin. Part of me was sick and tired of

America. I wanted to go to a place with a natural, pre-modern

lifestyle. Thailand was about as pre-modern as you could get.

One morning, as I was going on my alms round, it struck me that I was

living a hunter-gatherer's lifestyle. We were not allowed to store

food; we didn't grow crops. We ate what we got that day, that's it.

One hour a day is dedicated to food, and then you're free for the rest

of the day.

After breakfast, what happens?

We clean up, and everyone goes back to his hut. We meet again at about

5 p.m.

And during the day?

Mostly it's meditating. Some reading. I limit myself to two hours of

writing.

There's no bed in your hut, just a mattress

that you roll out every night. There's also a computer and printer. Do

you get e-mail?

No, but one of our supporters set up a web site:

http://here-and-now.org/watmetta.html.

You said that people here gather together

at 5 p.m. Is that for Happy Hour?

It's a question and answer period for visitors. Then people have free

time until 8:00, when we have a chanting session, which lasts about 20

minutes. Then there's an hour of group meditation and usually a Dhamma

talk [the teaching of the Buddha].

Do

you spend any of your meditation time reflecting on what you'll say?

Do

you spend any of your meditation time reflecting on what you'll say?

Very little. The Forest tradition places a lot of emphasis on

concentration practice, getting the mind to stay with one object. So

that's a lot of my time. And of course, if you're sitting for long

periods of time, pain is going to come up. Then the mind creates

issues about the pain. Dealing with that is the Buddha's First Noble

Truth: There is pain in life. There is suffering in life. I think the

reason he focused on that is that if you sit with your pains and

suffering, if you have the tools of concentration and mindfulness, you

start seeing these issues in your mind.

How is that different from therapy?

The purpose of therapy, Freud said, was to take neurotic individuals

and return them to an ordinary level of unhappiness. The purpose of

meditation is to take you from that ordinary level of unhappiness to a

place where there is no unhappiness and no suffering.

Do the people who come here bring

psychological baggage with them?

The monks are a pretty self-reliant group. It's the visitors who come

with deeper psychological wounds.

What kinds of questions do visitors ask

you?

Oh, everything from meditation questions to relationship questions.

How to deal with their kids, how to deal with their parents. How to

get out of an unhealthy situation. How to maintain one's commitment in

a situation that's difficult. "Should I go for that raise, or should I

find more time to meditate?" I tend to say, "Take more time to

meditate. You don't need that much money."

Almost 30 years ago, you embarked on a path

that took you away from the mainstream. You don't commute, you don't

have a 9-to-5 job, you don't have credit cards, and you don't have a

family. Does the path you've taken limit your ability to deal with the

problems people face?

I focus on what I can offer by being outside the rat race. During all

those years in Thailand, it was healthy for me to be around people who

didn't have typical American neuroses. You get to see your own

neuroses writ large because you're the only one in the area who's got

them. Until you say, "This is really dumb."

When do you go to bed?

Usually about 11 or 12.

You only get four or five hours of sleep?!

That's plenty. Meditation takes away a lot of the stressful need for

sleep.

Do you nap?

In the late afternoon.

Many people see Buddhism as anti-pleasure:

no drinking, no drugs, no debauchery. These are a few of my favorite

things. Do you ever miss them?

The biggest loss for me was classical music. I was hooked on classical

music. When I got stoned and listened all those years ago, that was my

idea of a good time.

When I began to meditate, I'd start getting into these states where I

felt the same sense of rapture I got from a really good performance of

classical music. I thought, "Oh my gosh, I can get this sensation just

by sitting here and breathing." In the past I had to worry about my

stereo and if my records would get scratched. I needed all that stuff

around just to get a pleasure fix.

Do you ever listen to classical music?

It's against the rules. When I go home, Dad has it on all the time, so

I hear it then. Occasionally Brahms or Mahler goes through my head.

But it gets so that you don't miss it.

What was the last movie you saw?

I saw the first Lord of the Rings on a flight to Thailand, but I

didn't hear it. There's a rule against watching shows; you're supposed

to be turning inward.

Are you allowed recreation of any sort?

For us, recreation is going out into the wilderness. Sitting on the

edge of the Grand Canyon and meditating, opening our eyes every now

and then, looking at the Grand Canyon, and meditating some more. We do

a lot of walking meditation; it's really emphasized in this tradition.

When I get a chance, or when I've had enough of the monastery, I go

out and hike around awhile.

What else do monks do for exercise?

A lot of sweeping up. Some Western monks and modern Thai monks do yoga

in their rooms.

But you can't say, "Hey, I've meditated all

day, I just want to toss around a football."

No.

Are you allowed to read for pleasure?

You get so that you're not interested in fiction. The only fiction

that I read nowadays is by my friend Jeanne Larsen [Class of 1971, the

author of three historical novels set in China] and Harry Potter.

Why Harry Potter?

I thought the books taught good lessons about loyalty, integrity, and

such things.

So Harry Potter's okay, Robert

Ludlam's not okay?

I have to use my judgment. Is what I'm reading getting in the way of

my meditation? If I find myself closing my eyes and seeing visions

that are not helping me at all, then it's obviously something I should

be not be reading.

Do you keep up with the world?

Only in the last year or two. I get The Nation and The

Guardian Weekly. I really liked all those years in Thailand when I

didn't get any news. For my first eight years, the only international

news that came out to the monastery was "Elvis Presley died" and

"Skylab is falling."

Did it take a long time to adjust to a

celibate lifestyle?

The first hurdle you face is not wanting to take care of it, the

attractiveness of lust itself. But after a while I began to realize

that I was suffering because of this. But if I focused on the lust

itself, rather than the object of the lust, I began to realize lust

was not that good a thing to have in my mind.

Do you ever feel lustful?

No.

Never?

You have meditation to take care of it. As soon as lust comes into the

mind, you've got to take care of it.

You sound so pragmatic.

It's very pragmatic. That was one of the lessons I got from Ajaan

Fuang: Get over the drama and sit down and do the work. I remember the

first time he said to me, "Okay, we're going to meditate all night." I

said, "My God, I can't do that! I've been working hard all day!" He

said, "Is it going to kill you?" No. "Then you can do it."

What about the simple desire for touch? Can

non-monks touch you?

Women can't. With men, it depends on how they're going to touch me. No

lustful touching.

Some people assume monks have transcended

human feelings and never have "negative" feelings such as anger and

greed. Do you ever get pissed off?

Occasionally there are irritations. A woman I taught became convinced

I was sending her subliminal messages. She thought I wanted to leave

the monastery and marry her. I tried to make it clear I wouldn't, but

she kept insisting I was giving her subliminal messages. I said,

"Look, you're not my student anymore. I'm sorry, this is not working

out." She thought I just said that because there were other people

around. So she started coming back. I must admit I was irritated. But

she finally got it.

What about the lesser frailties. Do you

have any vanity? Do you ever find yourself spending too much time

getting your robe to look just right?

The robe is pretty cut-and-dried. There's not much I can do about it.

Pride?

A little bit. I was editing my Dhamma talks, and every now and then

I'd come across a phrase and think, "that was pretty cool."

Do you have fears?

I'd hate to die before this place got established.

Do you ever have sleepless nights?

The last sleepless night I had was when one of my monks disrobed. I

kept thinking, "What did I do wrong?" I thought about it lying down

for a while, and then I'd get up and walk around for a while. Then I

sat down for a while.

There was a point in which I realized, "This is ridiculous. I'm not

getting any answers. So I might as well stop the questioning for the

time being." That's one of the skills you learn during meditation. If

you're asking questions, and there are no answers coming, just stop

asking. It's not time for the answer yet.

Do you ever feel guilt?

No.

Was that a difficult emotion to get rid of?

Yeah, that was probably a big one. But in Thailand, there is no guilt.

It's totally a shame culture ("Don't do that; it embarrasses us in

front of the neighbors"), but not a guilt culture ("Don't do that; it

hurts me when you do that"). Guilty feelings started feeling really,

really dumb. People function well and live perfectly normal lives

without it.

Did you pick up shame as a replacement?

If I do something I really know I shouldn't have done, then I feel

ashamed.

How do you deal with the shame when you

feel it?

Ajaan Fuang taught us that we can't just sit around and stew. The idea

is: you've noticed you've made your mistake; don't repeat it. That's

the best that can be asked of a human being.

Do you also believe in atoning?

You ask forgiveness of the person you've wronged.

In the Thai language, monks are referred to

not as people, but as "sacred objects." Do you view yourself as a

sacred object?

No.

How do you view yourself?

As a person. Despite this weird outfit, there's a human being in here.

Are there aspects of Buddhism that are

still mysteries to you?

I'd like to know what full enlightenment is like.

Do you ever, ever think about disrobing?

Bea Camp [Class of 1972] came to visit me one time in Thailand. She

and her husband David Summers [Class of 1971] were working for the

U.S. Foreign Service in Bangkok. They filled me up with all the news

of our old mutual friends–

careers that didn't turn out the way people had planned, divorces,

separations, disappointments. David asked me, "Have you ever regretted

being a monk?"

And I said, "Well, the thought never crossed my mind, and certainly

not now."

One final question. When you were in

Thailand, was there a "Eureka!" moment when you thought, "I've got

it"?

Monks can't talk about their attainments.

What if I say "please"?

(Laughter).

Playwright Rich Orloff lives in New

York.